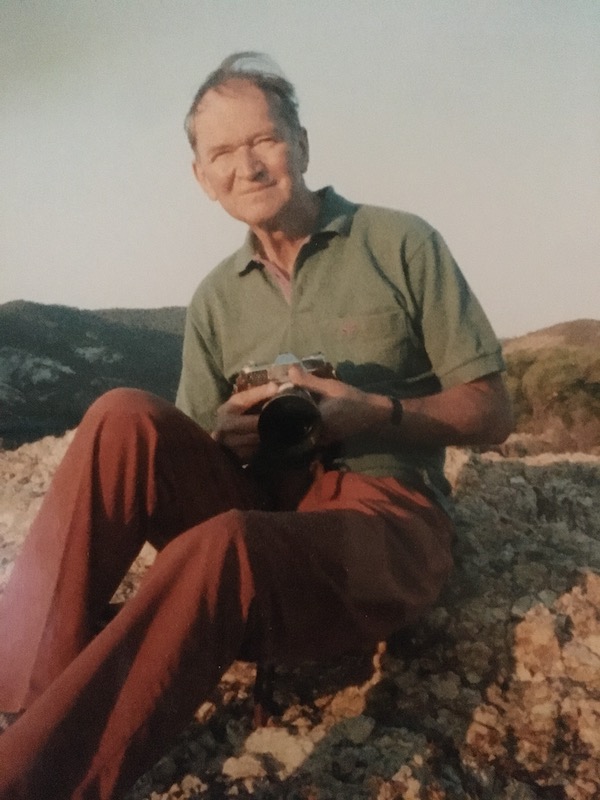

The Asklepion Snake – in memory of Denis Dunbar Gibbs

Sarah Gibbs submitted this article that she wrote today in memory of her father, Denis Dunbar Gibbs, Physician (and passionate about medical history), on the anniversary of his death on 8th January 2015.

My father was, to take the words from my brother Nicholas’s tribute to him at my father’s funeral, ‘a great and learned man with an understanding of the sum total of philosophy, history, science and technology of mankind – hearing in it the word of God and bringing healing and comfort to many thousands of people’.

A great man to remember on this day when, five years ago, he left this world suddenly, yet peacefully.

I wanted to write about something here that would be ‘special’ to my father’s memory and I have chosen The Asklepion Snake. Asklepios, son of Apollo and Coronis, was a God of Medicine in ancient Greek religion and mythology. In fact, he was so good at his job of healing that Pluto, God of the Underworld, became rather cross that Hades, the kingdom of the dead, became more depopulated as Asklepios kept saving people from dying.

The rod of Asklepios, a snake-entwined staff, remains a symbol of medicine today, and it permeated throughout my father’s life, both professionally and personally. On the day of his funeral we arranged for the floral arrangement on his coffin to be in the shape of the Staff of Aesculapius (Latin spelling).

Denis was reminded everyday of Asklepios via his charming bookplate, creatively designed for him by a local artist from Wallingford. And a distinctive weathervane that sat on top of his outside garden library that featured a single snake (the symbol of Asklepios) and a cockerel (the symbol of Hippocrates, Greek father of medicine). It was forged for my parents at a local forge in Clifton Hampden.

Whilst clearing out my father’s study we came across a buried file. It contained various articles about Asklepios, Hippocrates, and photos and travel writings about the island of Cos.

My parents visited Cos at least twice and my father has documented their visits with beautiful photos of the Temple of Asklepios (4th century BC). The ancient Greek Temples of Asklepion have been compared to the modern spa, sanatorium or ‘health farm’.

Hippocrates used to sit under the shade of a great plane tree in Kos Town main square. Descendants of the tree remain today with its huge branches being propped up by tubular scaffolding.

My father’s passion for delving deeper into the history of medicine, archaeology, and particularly Hippocratic medicine, led him to the ancient site of Cnidos in Turkey, just over the Aegean Sea from Cos. It was here that a rival school of doctors taught and practised in the 5th century BC.

I will leave you with an article that Denis wrote about Cnidos (typed on a typewriter) that he submitted into a travel writing competition in 1989 in the BMA News Review, prize a trip to Thailand.

The article wasn’t published. But it has left me with a keen desire to visit Cos and Cnidos, and to follow in the footsteps and soul of my father who was such a great and distinguished man of Medicine and Healing himself.

Cnidos – forgotten cradle of medicine.

Cos, the island of Hippocrates, is a place of pilgrimage for doctors. Viewed from the temple of Asklepios on Cos the mainland of Turkey lies only a few miles across the Aegean sea. Jutt vatting from this Anatolian coast-line, at the tip of the narrow and mountainous Datca peninsula, is the site of ancient Cnidos, where a rival school of doctors taught and practised in the 5th century B.C. From Cos it looks tantalisingly close but, without a personal yacht handy, the journey takes days rather than hours.

One approach is from the island of Samos, north of Cos, whence boats ply daily to the Turkish resort of Kusadasi. After a digression to Ephesus, we found a local bus to take us South to Bodrum, one-time Helicarnassus. We swished comfortably across the alluvial plain of the Meander river, while the courteous conductor was ever ready to sprinkle passengers with eau-de-Cologne, distribute juicy cherries and respond instantly to requests for ice-cold drinks.

Guide books recommend that Cnidos is best reached by sea from Bodrum, rather than along a tortuous road from Marmaris. The fates propitiously ensured that we arrived in Bodrum on the evening before the once weekly trip to Cnidos was scheduled. A strong local wind, the meltem, often blows hard from the north, so that the coast-hugging craft of the ancients had to be sturdily constructed. The tradition of quality in locally built boats continued in Bodrum. In such a caique we had a rough but safe passage across the Ceramic gulf, rounding the cape to the welcome haven of the south-facing harbour at Cnidos. When Cnidos flourished there were two fine harbours, one where naval triremes anchored and the other a busy commercial port. The two harbours with their partly surviving ancient moles are still overlooked by a magnificent natural amphitheatre, where lie the ruins of the city of Cnidos.

The attraction of Cnidos stems from its natural setting, relative remoteness and the unspoilt beauty of the arid and mountainous coast, as well as from the importance of its past associations. In antiquity Cnidos was famed for great works of sculpture, in particular the naked marble of Aphrodite, the creation of Praxiteles. This alluring Hellenistic tourist attraction had been rejected by the Coans in favour of a more modest clothed version which they selected for Cos. This statue, along with most others at Cnidos, disappeared. The lion of Cnidos is an exception. Until the last century it sat commandingly above the entrance to the southern harbour, but it is now displayed in the more accessible but far tamer environment of the British Museum.

Can the modern visitor discover any clues that Cnidos was an important medical centre in the ancient past? In the ruins and their environs stone pillars encircled by sculpted serpents provide the most direct and evocative symbols of a past medical tradition at Cnidos.

PS: A photo of the Lion of Cnidos, one of the original great works of sculpture from Cnidos site (now displayed in the British Museum), used to hang in the upstairs bathroom at my parents’ home at Kingsweston. For a long time I was ignorant of its significance, and now, very happily, I understand.

* For this article I have used the Greek spelling of Asklepios, rather than English spelling of Asklepius

** I have used the spelling of Cnidos that my father used in his travel article (rather than Knidos)

*** I have used the spelling of Cos that my father used in his travel article (rather than Kos)

**** The folder of beautiful photos that my father took at Cnidos, that included, significantly, a cockerel that happened to be wandering around the site on the day my parents visited, is with the scanners at the moment so sadly unable to include photos here

- Wikipedia – Asclepius

- Wikipedia – The Hippocratic Oath – historically taken by physicians and beginning with ‘I swear by Apollo the Physician and by Asclepius and by Hygieia and Panacea and by all the gods…’

- Wikipedia – Knidos – for my article I have kept with my father’s spelling of Cnidos