Gibbs Family Tree

Gibbs Family Tree

Obituaries and Press Articles following Christopher Henry Gibbs death on 28th July 2018

The Times

July 31 2018 - Christopher Gibbs obituary

The Times

July 31 2018 - Christopher Gibbs obituary

Gibbs in 2006 with some of his antiques in one of

the sales rooms of Christies in London

One night in the summer of 1968 Christopher Gibbs was partying

hard with Mick Jagger and Keith Richards at a South Kensington

nightclub. At about 2am Gibbs suggested that they adjourn to

Stonehenge to watch the sun rise.

Piling into Richards’s chauffeur- driven Bentley with the two

Stones, Marianne Faithfull and the American singer Gram Parsons,

the party arrived just in time to watch the sun come up over the

prehistoric monument, “all gibbering with acid”, as Gibbs put it.

Still high on LSD, they went to a pub in Salisbury and breakfasted

on kippers.

It was a typical day in the life of the extraordinary antiques

dealer and socialite, whose appetite for drugs earned the

admiration of Richards, who conceded that even he could not keep

up. “He was crazy,” Richards recalled in his memoir Life.

“He’s the only guy I know who would wake up and break an amyl

nitrate popper under his nose . . . He was an adventurous lad. He

was ready to jump into the unknown.”

Richards particularly enjoyed staying at Gibbs’s apartment at

Cheyne Walk on the Embankment, not only because of the endless

supply of illicit substances, but also because he could indulge in

the remarkable library. “I could just sit around, look at

beautiful first editions and great illustrations and paintings and

stuff that I hadn’t had time to get into,” Richards recalled.

Yet Gibbs was more than a mere drug buddy to the Stones. He

helped Jagger to secure the high-society introductions that he

craved; showed him around the “palaces and estates” of rural

England when he was looking to buy a place; and introduced him to

Prince Rupert Loewenstein, who became the group’s financial

manager.

Beyond the Stones and their associates Gibbs had a far wider

circle, acting as style guru and playmate to many who occupied

fashionable society in the 1960s, whether or not they could

remember being there. His antiques shop off Sloane Avenue in

Chelsea furnished with great treasures the mansions of a

generation that also included John Paul Getty Jr and Lord

Rothschild.

He was once described as “part Montesquieu, part Beau Brummell and

part Baudelaire”, while the writer James Delingpole noted that

“with his silvery hair, well-cut but rumpled suit, and diffident,

vaguely ecclesiastical air, he more closely resembles an Anglican

dean than an acid-tripping ex-roué once known as the king of

Chelsea”.

In short, Gibbs was a purveyor of exceptional and intriguing

pieces who believed that taste itself was not something that could

be learnt. “It’s something you catch,” he said, “like measles or

religion.” His position as a style guru was assured when he became

an editor of Men in Vogue, which was published between

1965 and 1970, coinciding with the “peacock revolution” in English

men’s fashion. Being a dandy is what he excelled at. “You had to

be monumentally narcissistic and have time on your hands, and just

about enough money to do it,” he declared.

Christopher Henry Gibbs was born in 1938; he had a twin sister and

four older brothers. The family had made its fortune in the guano

industry (or, as the rhyme put it: “Mr Gibbs/ Made his dibs/

Selling the turds/ Of foreign birds”). His father was Sir Geoffrey

Cokayne Gibbs, a senior civil servant during the war who in

peacetime became chairman of Antony Gibbs & Sons, the family’s

merchant bank; his uncle, Sir Humphrey Gibbs, was governor of

Rhodesia during the Unilateral Declaration of Independence.

In 1947 Sir Geoffrey inherited the rambling Manor House and estate

at Clifton Hampden, Oxfordshire, which had been in the family

since the 1840s. Young Christopher recalled a childhood spent

boating on the Thames, swimming and shooting, while also

describing the thrill of pressing his young face up against

antique-shop windows. He visited Christie’s auctions when still in

grey flannel shorts; by 14 he was sporting velvet slippers and a

monocle on a blue ribbon.

At 15 he was expelled from Eton for “various offences . . .

illicit drinking, panty raids of other boys’ rooms — that sort of

thing”. His crimes included organising a group of boys to pilfer

books from Ma Brown’s antiquarian bookshop and sell them back to

her.

He was obliged to finish his schooling at Stanbridge Earls in

Hampshire, which he described as “a school for sensitive,

difficult boys”. It was followed by his first job, as an estate

agent for Knight Frank & Rutley. This was interrupted by

National Service with the army, but he lasted only three months

before being “booted out” as medically unfit (as a child he had

polio).

There were brief studies at the Sorbonne in Paris, while back in

London he lived opposite St Paul’s Cathedral, engaging in a

dubious flirtation with the property business. At 20, and with

£10,000 from his mother, he set up as an antiques dealer,

returning from buying trips to Morocco with “rugs, lamps,

djellabas, wall hangings and the name of the best hash dealer in

Tangier”.

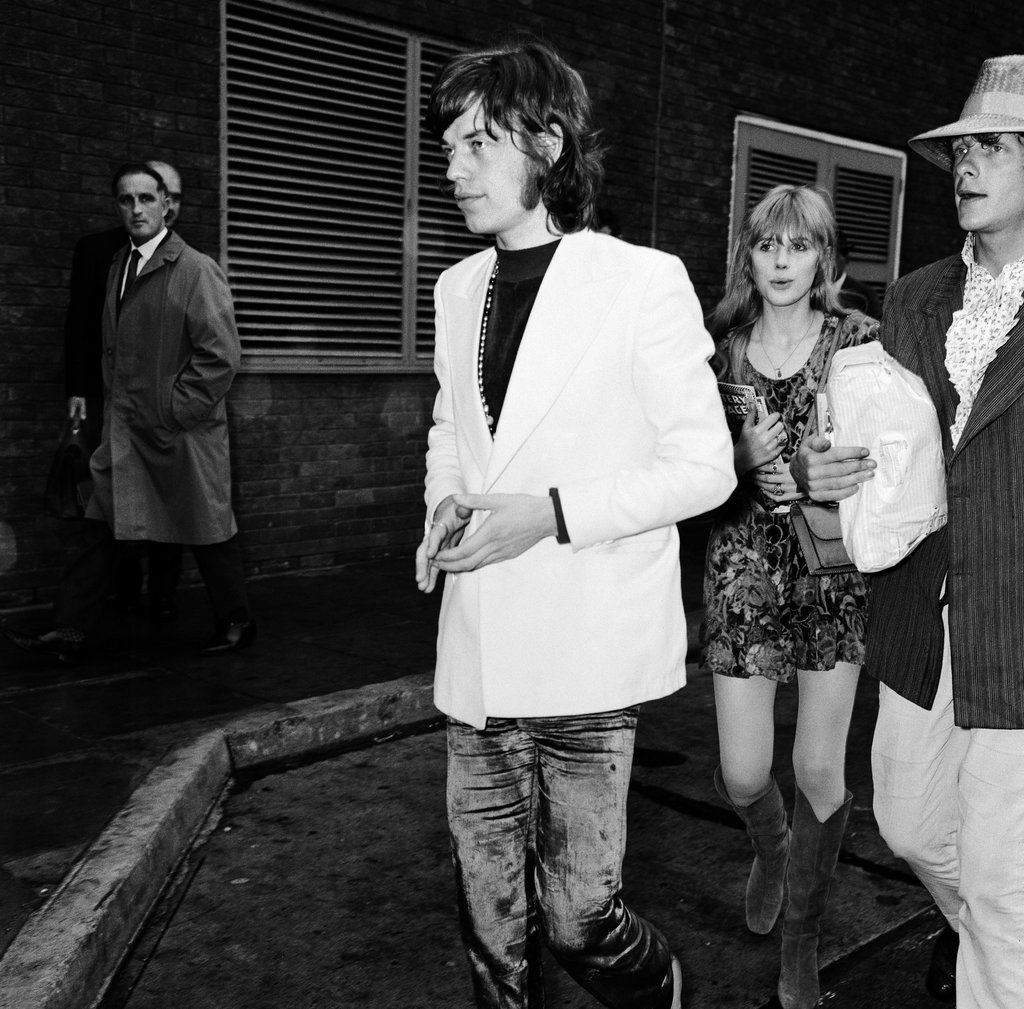

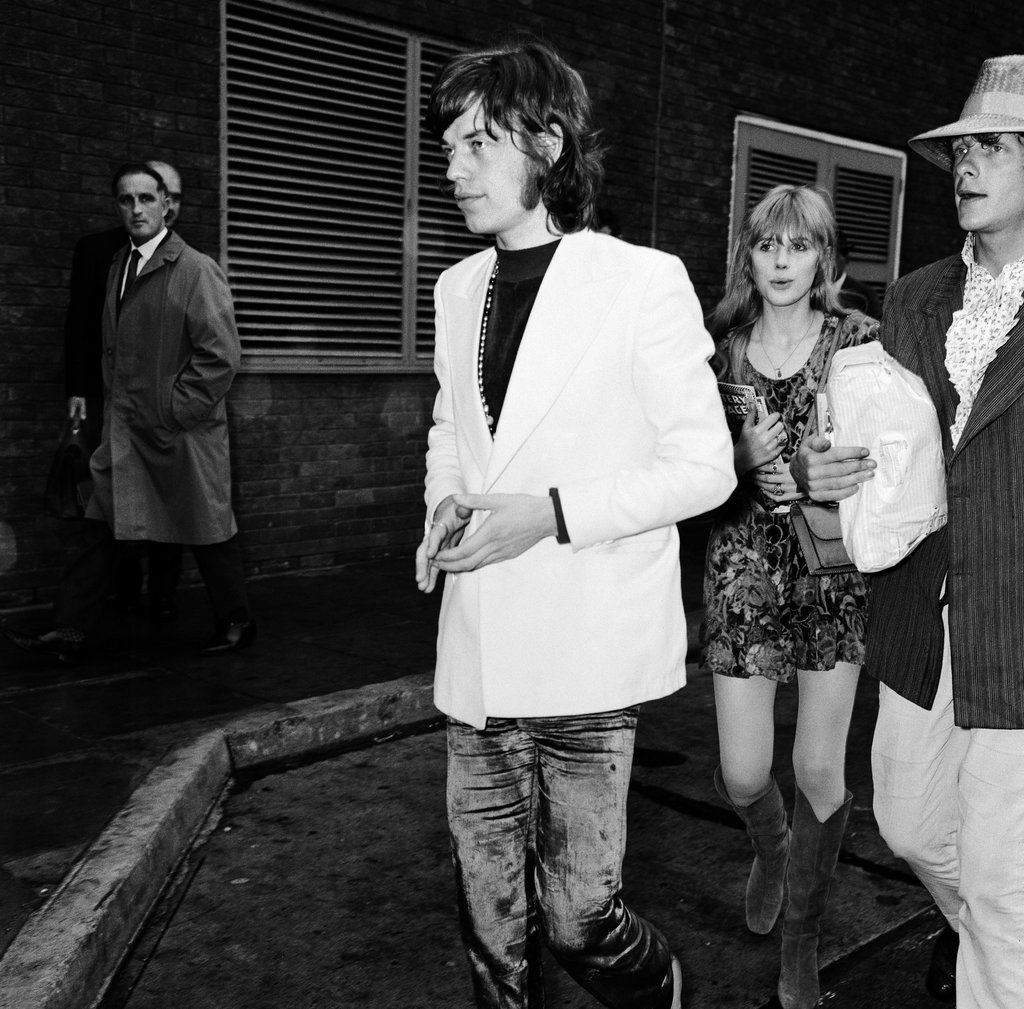

Gibbs with Mick Jagger and Marianne Faithfull

in Dublin, 1967

His first shop, opened in 1958, was a small place in Camden

Passage, a narrow, flagstoned alley in Islington. By 1962 he had

moved to larger premises in Elystan Street, Chelsea, where his

stock was distinguished by an eclectic richness. By now the

charming and sociable Gibbs was at the heart of the fashionable

Chelsea set. He was, by one estimation, “the most avant-garde

dresser this country has ever had”, favouring a flared trouser as

early as 1961 and with a wardrobe that mixed clothes brought back

from north Africa with the colourful reinvention of traditional

British tailoring found at places such as Blades in Dover Street.

His flat in Cheyne Walk hosted many of the gatherings of that

well-heeled bohemia, as well as providing the set for a

marijuana-smoking party scene in Michelangelo Antonioni’s film

Blow-Up (1966). Through shared acquaintances and Mrs Beaton’s Tent

in Frith Street, a common Soho haunt, his circle came to include

the Stones, whom he described as “merry company, funny, irreverent

and open-minded”.

He acted as a travel guide around Britain and Ireland for Jagger,

who in turn taught him to drive and asked him to be godfather to

one of his children. Gibbs took the singer and Marianne Faithfull

to stay with Desmond and Mariga Guinness at Leixlip Castle in Co

Kildare and in 1968 it was Gibbs who was responsible for naming

one of the era’s classic albums: the Rolling Stones’s Beggars

Banquet.

That same year he acted as designer on Nic Roeg’s notorious film

Performance, creating decadent sets for the rooms of the

fading rock-star Turner, played by Jagger with Pallenberg in

attendance. “There was so much hashish being smoked and so much

acid being dropped it’s hard to remember the decade, let alone the

film,” Gibbs remarked. His romantic associations included a brief

involvement with Rudolf Nureyev, whom he described as “quite

vigorous and stagy”.

In 1971 Gibbs moved to 118 New Bond Street, where he remained for

almost 20 years, before moving to Vigo Street and then, in 1998,

to Dove Walk, Pimlico. In all these buildings Gibbs displayed the

wonderful objects, often with extraordinary price tags, found in

the upper reaches of the London antiques trade. The Englishness of

the stock was enriched by different traditions and important

objects, often bearing an impressive provenance, and mixed with

items chosen because they were beautiful, rare or curious.

He relished the histories of Britain’s landed families, his

intuitive eye for objects of interest supported by a deep

knowledge of sales and catalogues that allowed him to make

discoveries hidden to others. The architectural historian John

Harris once suggested that were Gibbs to find himself on a desert

island, the book he would most like to have accompany him would be

his uncle’s annotated copy of the Complete Peerage. “I

like things with a past — and people, too,” Gibbs said.

His homes also revealed his gift for decoration: his houses in

Morocco; his apartments in Cheyne Walk and Albany; his country

house, Davington Priory, and, after 1980, the family’s Manor

House, which, despite being the youngest son, he inherited because

none of his siblings wished to move back.

His style proved widely influential, especially in America, and

affected the appearance of the glossy interior-design magazines,

such as World of Interiors, launched in the 1980s. His

knowledge and judgment were highly prized and he was a trustee of

the charitable trust established by his friend John Paul Getty Jr,

served on the arts panel of the National Trust, and advised the

Victoria & Albert Museum on the refurbishment of its British

galleries.

In 2000, after the death of his 90-year-old housekeeper, Gibbs

decided that he no longer needed the rambling spaces of the Manor

House. Among the objects in a two-day sale held in a vast tent on

the lawn were a Victorian stuffed two-headed lamb. Before leaving

for good he erected on a plinth a worn-out pinnacle from the

chapel at Eton College, which he had acquired through “one of the

beaks”. The Latin inscription explained that both he and the

pinnacle had been expelled.

His final destination was Tangier, where he established an elegant

home and garden on one of the mountain slopes overlooking the

Strait of Gibraltar. One visitor described him there as “wearing

wonderful kaftans”, adding: “And he looked like Moses walking in

the olive garden — very peaceful.” There were, however, some

things that he missed about England, he said, adding: “I get

homesick for snowdrops.”

Christopher Gibbs, antiques dealer, was born on July 29, 1938.

He died on July 28, 2018, aged 79

The

Telegraph 30 July 2018 - Christopher Gibbs, dandy, antiques

dealer, aesthete and friend of Mick Jagger – obituary

The

Telegraph 30 July 2018 - Christopher Gibbs, dandy, antiques

dealer, aesthete and friend of Mick Jagger – obituary

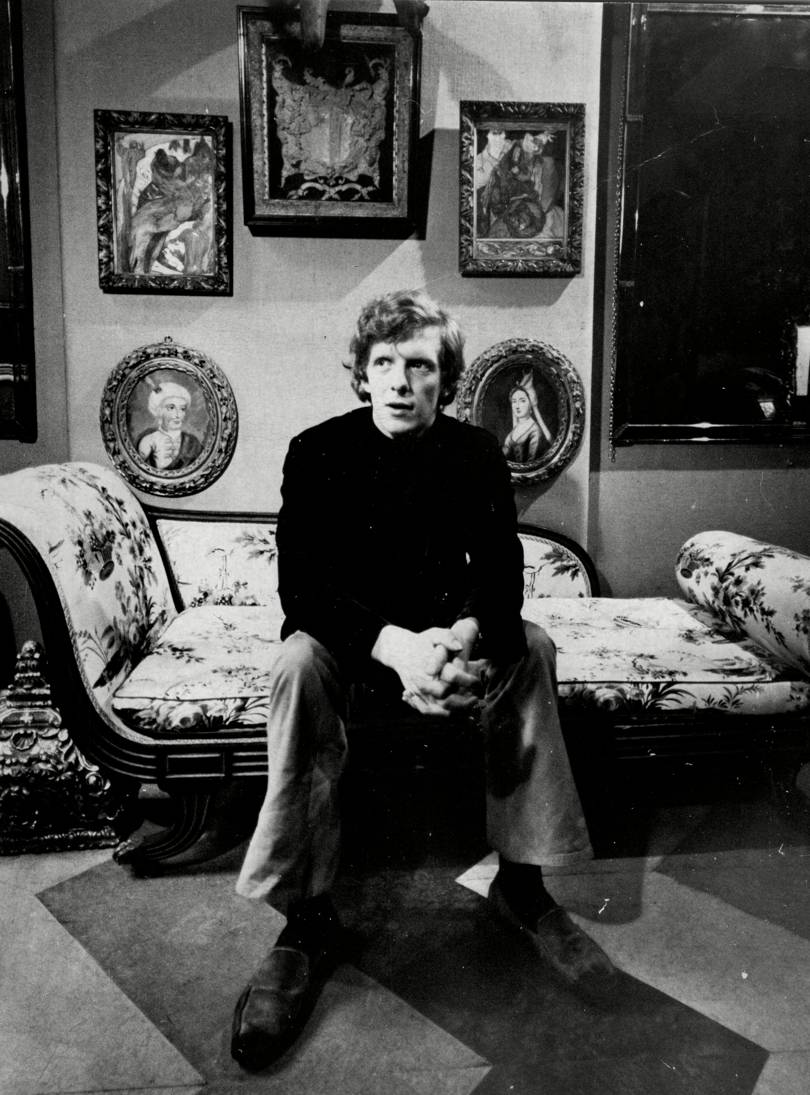

Christopher Gibbs in 1964

Christopher Gibbs, who has died aged 79, was an antiques dealer,

interior designer, bibliophile and aesthete who pioneered a style

of interior decoration often described as “distressed bohemian” –

a mixture of refinement, exoticism and well-worn grandeur.

A typical Gibbs interior might comprise a carefully chosen

assemblage of fine Georgian furniture, threadbare sofas, Chinese

blue-and-white ceramics, antique objets, church hangings, carpets

from the Maghreb and vibrantly clashing cushions and drapes. It

was a look that took years of antiquarian scholarship, poring

through the sales catalogues of auction houses, and eye-watering

prices to achieve. But Gibbs insisted that his aim was “to help

people make nice, cosy homes where they are going to live happy,

beautiful lives” – adding, “No, it’s not tongue-in-cheek. I mean

it.”

A quietly spoken man of considerable erudition and great personal

warmth, Gibbs became the arbiter of taste for a wealthy clientele

that ran the gamut from rock stars to aristocrats, and which

reflected his own extensive social circle. If conversation with

Gibbs could sometimes seem like a Himalayan expedition in name

dropping – be it mention of a famous pop-star, aristocrat, or an

“amusing German prince” (the banker Rupert Lowenstein, whom Gibbs

introduced to Mick Jagger, and who became the Rolling Stones’

business manager), it was because Gibbs did indeed seem to know

everyone.

In 1967 he was among the house-party at the infamous bust at Keith

Richards’s Sussex home, which resulted in the arrest of Mick

Jagger and the art dealer Robert Fraser for possession of drugs.

In the 1980s, he was largely responsible for rousing his friend

John Paul Getty Jr from the torpor in which Getty lay in the

London Clinic, being treated for drug addiction and depression,

and persuading him to make a donation of £40 million to the

National Gallery. In 2012 Gibbs advised and sourced much of the

furnishing for the restoration of Spencer House by his friend

Jacob, Lord Rothschild.

Christopher Gibbs was born on July 29 1938, the fifth son of Sir

Geoffrey Cokayne Gibbs KCMG and his wife Helen. Following in his

father’s footsteps, Gibbs was sent to be educated at Eton, but was

expelled, as he would later recall, “for drinking, panty raids on

other boys’ rooms, that sort of thing …” After attending the

University of Poitiers, and a short spell in the Army, he became

the hub of “the Chelsea Set” – a loose aggregate of young aristos,

public schoolboys and the more racy species of debutantes, who

frequented the Markham Arms in Chelsea, and whose principal

enthusiasms were clothes, inebriation and a rather self-conscious

slumming.

Gibbs was the dandy par excellence; as a 14-year-old at Eton he

had sported velvet slippers, a monocle and a silver-topped cane

with blue tassels and handed out visiting cards. He was said to be

the first person on the King’s Road to wear flared trousers, in

1961, and the first to wear kaftans. “He was very flash,” Nik Cohn

wrote in his book on British style in the Sixties, Today There Are

No Gentlemen. “Sometimes he just wore tight jeans or fancy dress,

like the others; but mostly his tastes were elaborate; suits with

double-breasted waistcoats and cloth-covered buttons, and velvet

ties, and striped Turkish shirts with stiff white collars, and

cravats. Above all, he had a passion for carnations and was

forever buying new strains, pink-and-yellow, or green-ink, or

purple with red flecks.”

In 1958 Gibbs made his first visit to Tangier, returning with a

stock of drapes, hangings and cushions, with which he stocked his

first antiques shop in Chelsea, selling decorative objets and

furniture. Fascinated, as he put it, “by the mixture of the grand

and the raffish and the fast and the chic”, Gibbs became the

aesthetic centre of a group that embodied the socially fluid and

hedonistic mood of Sixties London.

The set included the Rolling Stones (it was said to be Gibbs who

“initiated Mick Jagger into the arcane mysteries of high camp”),

the heir to the Guinness fortune Tara Browne, the men’s fashion

designer Michael Fish and the American avant-garde film director,

occultist and Aleister Crowley enthusiast Kenneth Anger (“He’d

hate me to say it,” Gibbs once remarked, “but Kenneth’s a cosy old

thing.”). Robert Fraser would credit Gibbs as having invented

“Swinging London”.

Gibbs’s Cheyne Walk home became a salon for the hip elite. It was

used by director Michelangelo Antonioni as the set for the party

scene in Blow-Up, and Anger also used Gibbs’s home to shoot some

of the scenes of his infamous masterpiece Lucifer Rising.

In 1968 Gibbs was employed to design the interiors for Donald

Cammell and Nic Roeg’s seminal Sixties film Performance, about a

past-it rock star, Turner, played by Mick Jagger. Cammell had

stipulated that the interiors should be decorated “predominantly

in the Gibbsian Moroccan manner, furnished with strange and

beautiful things,” suffused with a glamorous decay, “the dust in

its crannies of a refined sensibility”. It was the style that

Cammell had employed in designing Brian Jones’s flat in Earls

Court.

Gibbs furnished Turner’s rooms with mats and hangings from

Morocco, a bedspread from the Hindu Kush, a marbled bath with 17th

century Japanese dishes, and tiles designed from a Persian carpet.

“I wanted something mysterious and beautiful and unexpected,

exotic and voluptuous and far away from pedestrian; some hint of

earthly paradise. It also had to be done in four and half minutes

on four and a half pennies.”

An enthusiastic consumer of marijuana and LSD, Gibbs nonetheless

retained a tenacious work ethic. “I definitely suffer from the

blown-mind syndrome,” he told the writer Paul Gorman, recalling

the Sixties. “The only thing I’ll say in my favour is that I was

practically the only person I knew who actually went to work at

nine o’clock in the morning … because I had a job, my own

business, and I realised that, if I didn’t, I wouldn’t have any of

those things.”

For years Gibbs occupied a set in Albany, the most exclusive

address in London, where his friend the writer Bruce Chatwin once

lived in the attic “with a Jacob chair from the Tuileries and the

18th-century bedsheets of the King of Tonga adorning the wall.”

In 1972 he bought a former Benedictine nunnery, Davington Priory

in Faversham, where for three years his houseguest was the

mercurial David Litvinoff, an intimate of Lucian Freud, the Kray

Brothers and the Rolling Stones, who acted as “director of

authenticity” on Performance.

Litvinoff became so intolerable that Gibbs was finally obliged to

move out. Shortly afterwards, Litvinoff killed himself there with

an overdose of sleeping pills. “He left me a note, which I found

three months later, hidden in some shirts,” Gibbs recalled. “He

loved blues music. It said ‘I’ve made eight tapes for you in such

and such a box; please send another tape marked X to somebody in

Australia’. No question of ‘I’m terribly sorry to have been such a

nuisance’ or anything like that.”

Gibbs later sold the house to Bob Geldof, who planned Live Aid

there.

In 1980, following his mother’s death, Gibbs took over his

childhood home, the manor house at Clifton Hampden in Oxfordshire,

which had been built for his family in the 1840s. He sold the

house in 2000, moving to a small cottage on the estate. An auction

of the house’s contents in 2000, which raised £3 million, included

a dining table cut from a slice of wood, thought to be one of the

first pieces of mahogany transported to England from the New World

by Charles II’s navy in the 17th century, and an embroidered

Elizabethan purse that belonged to the first Lord Yarmouth,

treasurer to James II, containing a fragment of the monarch’s blue

silk garter enclosed in a wisp of paper bearing the words, “King

James’s Garter – I touch and God cures’’.

Gibbs was a connoisseur of English church architecture, the

decorative arts, antiquarian books and the gardens of stately

homes. His friend John Richardson, Picasso’s biographer, described

him as being “in the tradition of English cognoscenti – like an

18th-century English parson who knew more about Etruscan vases

than anybody in the British Museum.” He disdained bad manners,

kitsch, the “floridity” of the super-rich, and television sets.

In 2006 he auctioned off the last of his stock at Christie’s and

retreated to Tangiers, where he bought a home overlooking the

city. This he furnished with characteristically eclectic taste

with such items as a mid-17th-century painting attributed to Luca

Giordano, shabby sofas, antique marbled tables and a collection of

whips. While admitting that he sometimes got “homesick for

snowdrops”, Gibbs admired Tangiers as a place, he once said, where

you could feel “the ancient world still kicking along”, and where

his aesthetic sense was tempered by “the basics … Here they can

cheer things up with a bunch of flowers or a small piece of

needlework.”

There he concentrated on cultivating his garden, and his duties as

a church warden at the city’s Anglican church, St Andrew’s. A

visitor to Gibbs’s home noted that “he was wearing wonderful

kaftans, and he looked like Moses walking in the olive garden.”

He never married.

Christopher Gibbs, born July 29 1938, died July 28 2018

Vogue July 31

2018 - Hamish Bowles Remembers Christopher Gibbs, The

Quintessential British Dandy and Tastemaker to Generations

Vogue July 31

2018 - Hamish Bowles Remembers Christopher Gibbs, The

Quintessential British Dandy and Tastemaker to Generations

Christopher Gibbs, 1966

“Taste is difficult to define,” opined Min Hogg, the exigent

founding editor of World of Interiors, “but his is absolute

perfection.” She was talking of her great friend Christopher

Gibbs, tastemaker extraordinaire, who has died on the cusp on his

80th birthday.

The fifth son of the Hon. Sir Geoffrey Cockayne Gibbs, KCMG and

his wife Helen Margaret Leslie CBE, Christopher Gibbs was a

well-born Renaissance man with an unmatched eye for aesthetics and

a talent for friendship and the mot juste. His weighty words were

dispensed with the effortless elegance that he applied to all

aspects of his life, from faith to clothing, to collecting and to

romance, as he reached for a turn of phrase that could be by turns

Firbankian, Mitfordian, or Hogarthian. He was expelled from Eton

for Rabelaisian antics—“illicit drinking, panty raids of other

boys’ rooms—that sort of thing,” as he wryly recalled, and later

attended the University of Poitiers, followed by a brief stint in

the army.

But it was a trip to Morocco that was to prove an epiphany. There

he discovered the “chimeric city” of Tangier. “I was a young

fellow,” he told The New York Times, “and I came in the spring

with an old-fashioned friend who had letters of introduction.” It

was, as he discovered “a mystic hangover,” a place where “the

ancient world [was] still kicking along.”

After that first Tangier foray, Gibbs returned to London laden

with Moroccan textiles and rugs and beautifully hand-crafted

objects with which he stocked his first antiques emporium on

Sloane Avenue. He was 20.

At a time when penurious aristocrats were still demolishing

unwieldy stately homes or at least divesting them of some of their

contents, the well-connected Gibbs was uniquely placed to sleuth

and gather the spoils and market them with seductive style to a

generation of deep-pocketed fellow trendsetters, from a gaggle of

Gettys and Lord Rothschild to Bryan Ferry and Mick Jagger (who

hung out with him, as he once playfully confessed, “to learn how

to be a gentleman”).

Gibbs’s avowed aim, as he modestly noted, was to “help people make

nice cosy homes where they are going to live happy, beautiful

lives.” In fact, he shaped the taste of a generation, appreciating

the potency of provenance and patina, and handling scale like no

one else. He venerated the splendid and the curious and the humble

in equal measure—aesthetic beauty and craftsmanship and the love

that had been expended on objects were what attracted him, and he

set the bar for generations of insatiable collectors and

aesthetes. A visit to his emporium was invariably a lesson in

history. His erudition was astonishing, “in the tradition of

English cognoscenti,” as his friend Sir John Richardson noted,

“like an eighteenth century English parson who knew more about

Etruscan vases than anyone at the British Museum.” Above all, he

disdained the ‘floridity” of opulent taste; Tangier, he averred,

had taught him the beauty of “simplicity.”

In a Gibbs scheme a console of writhing old golden volutes hauled

back from a Grand Tour by some eighteenth century English

aristocrat for his Palladian palace (and still bearing its

original age-dulled and flaking flinish) would be juxtaposed with

pots made by villagers in the Rif mountains where he built a

bewitching adobe retreat. Damasks were faded, silk velvet was

balding, a grand Victorian club chair (once doubtless home to some

distinguished writer or politician’s sturdy bottom) would be so

threadbare it was practically spilling its horsehair innards,

garden flowers were arranged more or less as they fell. “I like

things in their natural state,” he once explained, “people

especially…objects and people that are unmonkeyed with, that are

themselves, not trying to be something else.”

“Part Montesquieu, part Beau Brummel, and part Baudelaire,” Gibbs

was at the throbbing heart of Swinging London, attracted, as he

recalled to “the grand and the raffish and the fast and the chic,”

although he always understood that hard work was the only thing

that would sustain and support his passion for beautiful people

and things. He knew and was in turn beloved by a who’s who of the

great style-makers of the 20th and 21st centuries.

His Cheyne Walk flat was the setting for the marijuana party scene

in Antonioni’s Blow Up, (“I thought you were supposed to be in

Paris,” an irate David Hemmings— as a character based on David

Bailey—says to the period’s uber model Veruschka. “I am in Paris”

she replies, apparently stoned out of her mind). Kenneth Anger

also shot some scenes for his 1971 cult classic Lucifer Rising

there. Gibbs defined the look of Swinging London in the haute

boheme setting that he designed for Nicolas Roeg’s 1970

Performance starring Mick Jagger, Anita Pallenberg, and James

Fox—sets that exemplify his signature hippie de luxe mix of vastly

scaled antiques, quirky objects, and Moroccan textiles. “I wanted

something mysterious and beautiful and unexpected,” he explained,

“exotic and voluptuous and far away from pedestrian: some hint of

earthly paradise.” It could describe any of the magical

environments that he created for himself.

If it was happening in the ’60s, Gibbs was there: he was at the

party where the Stones were busted and Marianne Faithful was

cavorting with a Mars Bar, and he took the band to Tangier where

they hung out at the louche Café Hafa and discovered the unique

cadences of indigenous Moroccan music. When he hosted a fashion

show for Janet Lyle and Maggie Keswick’s fashion house of Annacat

in his Regency flat in 1967 beauteous British aristocrats modeled

the clothes in his tapestried drawing room before the gratin of

with-it society: David Bailey brought Catherine Deneuve, Marianne

Faithful simpered, and Private Eye’s editor John Wells read the

order of show to the accompaniment of Dudley Moore at the piano.

Gibbs was the quintessential dandy. He is credited as the wearer

of the first flared pants for men (in 1961), of flowering

patterned shirts and Regency revival jackets and Moroccan caftans,

and was the poster boy for his friends’ menswear fashion brands

(including Michael Rainey’s Hung on You, Rupert Lycett Green’s

Blades, and Nigel Waymouth, Sheila Cohen, and John Pearse’s Granny

Takes a Trip). Gibbs confessed to being “monumentally

narcissistic” at the time, and recalled that he might spend 40

minutes on the phone with friends discussing which particular tie

(kipper-wide, from Mr. Fish), to wear that day. In the latter half

of the ’60s Gibbs parlayed his sartorial know-how as the editor of

the shopping guide in the quarterly Men in Vogue supplement of

British Vogue. In later life his grand bespoke finery was as

loved, well-worn, and battered as the objects he revered, and in

Morocco his caftans and lemon leather babouche slippers gave him

the appearance of a biblical seer.

Gibbs later exercized his interior taste in a set at Albany, the

storied apartment building built around the 1774 mansion designed

by Sir William Chambers for Lord Melbourne. A stone’s throw from

London’s Piccadilly Circus, and “the enticements of Soho, the

grandeur of St. James’s, [and] the comforts of Mayfair, to say

nothing of the canny tailoring of Savile Row,” it was, as Gibbs

noted, a place famed for its archaic house rules (“no pets, no

children, no whistling, no noise, and absolutely no publicity”).

It was the perfect London perch, and here Gibbs joined a roster of

past and present incumbents that has included Lord Byron, Baroness

Pauline de Rothschild, Isaiah Berlin, Terence Rattigan, Bruce

Chatwin, Sybille Bedford, Terence Stamp, Aldous Huxley, Fleur

Cowles, David Hicks, Garbo, and a fistful of prime ministers from

Gladstone to Thatcher.

By 1972 his success as a dealer of beautiful treasures was such

that he acquired rambling Davington Priory, a former Benedictine

nunnery built in 1153 in the English county of Kent. In 2000, with

great reluctance, he sold his family house in Clifton Hampden in

Oxfordshire and its contents in an epic sale at Christie’s (“it’s

quite a caper to keep a place like this going”), and retreated to

his Tangier homes.

He acquired El Foolk, the house of the beauteous artist Marguerite

McBey, a Philadelphian heiress who had created a farmhouse on

Tangier’s Old Mountain that would not have been out of place in

the Sussex Downs and commanded breathtaking views across the

Straits of Gibraltar to the coast of southern Spain. Gibbs opened

a double doorway from the living room into her former studio, but

otherwise kept the atmosphere intact and amplified it with a

layering of even more precious and idiosyncratic objects. With his

godson, the architect Cosimo Sesti, he later built a ravishing

Neoclassical villa in the neighboring gardens, and worked with

fellow aesthete Umberto Pasti to create new gardens of imposing if

always insouciant charm that soon grew to fecund splendor.

This new house, with its soaring volumes, was a showcase for

Gibbs’s bravura if nonchalant taste. The drawing room’s walls were

dappled in lime-wash the color of pulped tomatoes by a feisty

Frenchwoman who came up from Marrakesh expressly for the purpose;

underfoot lay a Tuareg straw and leather carpet. The room’s great

height was emphasized by a vast and handsome painting,

convincingly attributed to Luca Giordano, of “Hercules hoisting

the giant Antaeus,” in its original frame of chunky scrolls of

ebonized and gilded wood (the Caves of Hercules are to be found

just outside the city of Tangier). It hung above an Indian Regency

sofa with a faded pink linen cover hidden beneath an embarrassment

of cushions worked with Fez embroidery. Gibbs’s study was

essentially a conservatory that brought the sublime gardens

inside. “If you have a garden and you experience it through the

seasons,” he confided, “it holds you for life.” Gibbs’s partner in

life was the sumptuously beautiful Peter Hinwood who lived in his

own modest house in the gardens of the El Foolk property.

Possessed of very distinguished taste himself, through the decades

Hinwood has enjoyed careers as a model, (notably cast as a

motorbiking Lothario for an iconic ’60s Olivetti commercial), an

antique dealer of consummate refinement, and as an actor,

memorably portraying the original Rocky in The Rocky Horror Show,

clad in the briefest gold lamé shorts and muscle magazine

abdomens.

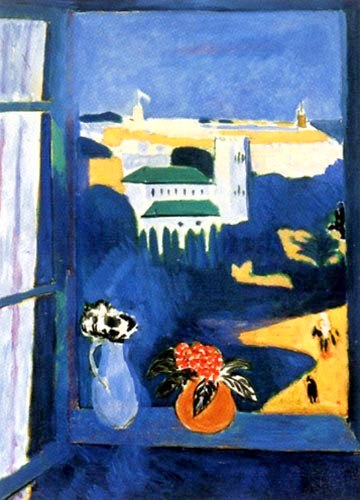

Gibbs was a pillar of the quaint church of Saint Andrews, built at

the turn of the century on the fringes of Tangier’s Grand Socco—“a

cool oasis in the city,” as he noted, “with texts from the Koran

woven into the reredos and the Lord’s prayer in Arabic round the

chancel arch. Its very existence—built by the Scots, painted by

Matisse— encourages a belief in miracles.” Gibbs’s faith was deep

and sustaining and was made manifest in his profound kindness and

generosity of spirit.

Gibbs was a pillar of the quaint church of Saint Andrews, built at

the turn of the century on the fringes of Tangier’s Grand Socco—“a

cool oasis in the city,” as he noted, “with texts from the Koran

woven into the reredos and the Lord’s prayer in Arabic round the

chancel arch. Its very existence—built by the Scots, painted by

Matisse— encourages a belief in miracles.” Gibbs’s faith was deep

and sustaining and was made manifest in his profound kindness and

generosity of spirit.

Christopher Gibbs died like a king of yore, in his beloved house

in his beloved Tangier, surrounded by friends, family, and devoted

retainers, in a room filled with auction catalogues and commanding

views across the orchard of datura and pomegranate trees that he

had planted and seen grow to fruition, the roiling Straits of

Gibraltar beyond, and the skies above the bright plumbago blue of

his eyes, those all-seeing eyes that had defined taste for half a

century and more.

Architecural

Digest - Remembering Christopher Gibbs

Architecural

Digest - Remembering Christopher Gibbs

The arbiter of bohemian style died this weekend

Christopher Gibbs, who died in Tangier,

Morocco, on Saturday, his 80th birthday, bestrode the aesthetic

world like a rock star, and not just because his clients and

friends were literally rock stars—among them, a very young Mick

Jagger, who once confided to a fellow guest at a dinner party

hosted by Gibbs, “I’m here to learn how to be a gentleman.” That

level of celebrity might come as a surprise, given that Gibbs was

an antiques dealer, not typically known as a glamorous career

choice, but he was something quite a bit more rarified than a

purveyor of beloved old things. He was a broodingly handsome,

wittily eloquent man whose quirky, funky, exotic, counterculture

taste, and vast curiosity influenced a generation of individuals

who fell passionately in love with what The New York Times once

called his “distressed bohemian style.”

Christopher Gibbs, who died in Tangier,

Morocco, on Saturday, his 80th birthday, bestrode the aesthetic

world like a rock star, and not just because his clients and

friends were literally rock stars—among them, a very young Mick

Jagger, who once confided to a fellow guest at a dinner party

hosted by Gibbs, “I’m here to learn how to be a gentleman.” That

level of celebrity might come as a surprise, given that Gibbs was

an antiques dealer, not typically known as a glamorous career

choice, but he was something quite a bit more rarified than a

purveyor of beloved old things. He was a broodingly handsome,

wittily eloquent man whose quirky, funky, exotic, counterculture

taste, and vast curiosity influenced a generation of individuals

who fell passionately in love with what The New York Times once

called his “distressed bohemian style.”

“I'm not interested in creating a dazzling impression of

richness,” he told The Guardian. “We can make do with

surprisingly little in life. It is best to have a few things which

are really nice. I don't approve of the mean look, but I do

approve of the spare look, where every little bit is telling.”

Some of the finest bohemians in the Age of Aquarius sprang from

posh backgrounds, and Gibbs, as a grandson of a knight, son of a

baronet, and a descendant of Blessed Margaret Pole, Countess of

Shrewsbury, the martyred Plantagenet heir to the English throne,

was a prime exemplar. An ancestor established the family fortune

by founding a successful London trading company in the 18th

century, and an uncle became governor-general of Southern

Rhodesia. Known far and wide as Chrissie or Dibbley, Gibbs threw

himself not into commerce or politics—he had been expelled from

Eton, he revealed, because of “illicit drinking, panty raids of

other boys’ rooms, that sort of thing”—but into dandyism, becoming

a Beau Brummel of his generation while also operating a buzzy

little antiques shop that he opened in 1958 at the tender age of

20. “Being a shopkeeper, I used to sell things sometimes,” said

Gibbs, who stocked Moroccan garments and textiles and the like

before expanding his stock into atmospheric antiques. “Then I used

to parade around in them.” As he told Life magazine in 1961, he

“encouraged friends to dig into their heirlooms, to wear old

clothes, to turn their backs on ugliness and conformism.”

A heroic 17th-century Italian painting, Fez

needlework cushions, an Anglo-Indian sofa, and a splash of

flowered chintz outfit the living room of El Foulk, Gibbs'

Tangier residence, captured by Miguel Flores-Vianna in his book

Haute Bohemians.

All that peacocking led to the so-called King of Chelsea being

hired to be editor in chief of Men in Vogue, a job that

allowed him to cover the sartorial, social, and swinging lives of

his circle of finger-snapping, hashish-smoking, LSD-dropping,

snake-hipped dandies, a heady brew of toffs, entertainers,

socialites, bright young things, and kohl-eyed sirens of both

sexes, from J. Paul Getty Jr. to Marianne Faithfull (which

explains why, later in life, biographers and historians relied on

his memories of that fertile, fantastic period he called “a time

of experiment, dope-fueled and acid-elevated”). He was painted

bare-chested by Patrick Procktor, photographed broodingly by Lord

Snowdon and David Bailey, and loved devotedly by Peter Hinwood,

the blond Adonis of The Rocky Horror Picture Show, who

became Gibbs’s life and business partner as well as an enormously

admired dealer and designer himself. “A man of great, great taste,

almost better than the master,” says AD100 interior designer Veere

Grenney, a part-time Tangerine and close friend, about Hinwood,

who, along with several nieces and nephews, survives Gibbs. The

dealer will be buried on Wednesday, August 1, at the cemetery of

the Church of St. Andrew in Tangier, following a funeral that,

appropriately enough, Grenney says will incorporate “Islamic

elements plus be in the Anglican tradition.”

Gibbs also created sets for the 1970 cult Nicolas Roeg/Donald

Cammell crime-drama Performance, which starred Jagger. “I

got a lot of things from Tangier,” the dealer explained in an

interview for Christie’s.“We had things made and sent over in a

hurry – materials both old and new. There was a lot of sleuthing

around the film hire places, sourcing what might help knit

together and work in the whole picture. The most complicated thing

was making the tiled wall in the bathroom, inspired by a

16th-century garden carpet in the V&A; it made the perfect

backdrop to the bathtub frolics.… The bed for example was based on

the story of the Princess and the Pea; many mattresses on top of

one another, and a mighty stack in multi-coloured velvets was made

and trundled north from Morocco.” His passion for the North

African kingdom had begun with a trip there in 1958, and he

remained enthralled by zellige, tadelakt, and Berber carpets for

the rest of his life, even though, as he once admitted, souk chic

had become a bit old hat.

His apartment at 100 Cheyne Walk, a seductively louche magnet

for London’s hip set, appeared in Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up

and Kenneth Anger’s Lucifer Rising. “The [drawing] room

was dominated by an enormous painting by Il Pordenone that had

previously belonged to the duc d’Orléans,” a biography of William

S. Burroughs, a Gibbs intimate, recounts. “A huge Moroccan

chandelier cast a thousand pinpoints of light over Eastern

hangings and silk carpets. In the summer, afternoon tea was taken

under the mulberry tree in a garden designed by Lutyens.” Cheyne

Walk was also where Gibbs hosted a famous party for Allen

Ginsberg, which Princess Margaret attended. So did Talitha Pol

(Mrs. J. Paul Getty Jr.) in a see-through dress that revealed a

total lack of undergarments. Unexpectedly powerful hashish

brownies (the recipe came from The Alice B. Toklas Cook Book)

were among the hors d’oeuvres, and Her Royal Highness ended up in

hospital with what was blamed on “severe food poisoning.”

Gibbs' Tangier dining room in a photograph by

Miguel Flores-Vianna from Haute Bohemians.

Though AD once described Christopher Gibbs Ltd. somewhat

blandly—“Eclectic and unusual items from the 17th century through

the 1960s”—it was, Canadian interior designer Colette van den

Thillart has recalled, “a Kunstkammer filled with the most

astonishing wonders…a vibrant yet gloomy forest of beauty.” It was

the sort of place one could find anything from a 19th-century

American whip that once belonged to Lord Rosebery (“It was

probably used for whipping slaves,” Gibbs blandly observed) to

what Manhattan decorator David Easton called “large eccentric

furniture,” such as a pair of 20th-century sofas copied from a

grandiose design by 18th-century architect William Kent or

bookcases so immense that they required a castle to suit them

properly. One could find Jagger poking around as readily as one

could glimpse Bill Blass, Pauline de Rothschild, or Lincoln

Kirstein; one of the salesmen, appropriately enough, had been

Bulent Rauf, the Turkish mystic. Simon Wells, in his book Butterfly

on a Wheel: The Great Rolling Stones Drug Bust, twigged

Gibbs’s taste perfectly, defining his haute-hippie chic as

“well-worn grandeur with vibrant treasures from Asia, the Middle

East, and Africa, particularly Morocco. Aware that much of Middle

Eastern art and decor resonated strongly with the psychedelic

experience, Gibbs was a much sought-after expert when pop people

turned their attention to decorating the interiors of their flats

and houses.” Jagger relied on Gibbs to decorate multiple houses

for him, having fallen completely under the dealer’s spell; Lord

Rothschild and Paul Mellon were fans too.

“It was a memorable experience to leave the hustle and bustle of

Bond Street, pass through that narrow darkened passage, to burst

into the high, top-lit treasure house of salivation,”

architectural historian John Harris recalled of Gibbs’s shop.

“Here would be found the genial and constantly creative Peter

Hinwood, one of whose roles was aesthetic arrangement and

juxtaposition, what one might call the shaking of the

kaleidoscope. I was always aware of how object answered object in

many sensitive ways, and there was always what might be called

creative rearrangements. I suppose the exhibit that evoked gasps

from all and sundry was Lord Iveagh’s sock cabinet from his

bedroom at Elveden Hall, Suffolk; its drawers still containing an

array of smelly socks wrapped around Sir William Chambers’s

designs for the cabinet, no less than the medal cabinet designed

for Lord Charlemont at Charlemont House, Dublin.”

Photographs of Gibbs’s residences, from Davington Priory in

Oxfordshire to El Foulk in Tangier, which was featured in Miguel

Flores-Vianna’s book Haute Bohemians, were widely studied,

ravishing more than one generation of admirers. Each home was a

shrine, Christopher Mason wrote in The New York Times in

2000, to the dealer’s “elusive brand of anti-decoration,

high-bohemian taste favored by self-confident Englishmen, a look

based on well-worn grandeur, disarming charm, and unexpected

contrasts. The magic is in the mix of masterpieces and

oddities—like an assemblage of refined and wild-card house guests

who mysteriously combine to create the ideal convivial

country-house weekend. The allergy here is to the banal, not to

dust.”

Gibbs reveled in a lifelong “delight in quirky objects whether humble or precious,” Hamish Bowles of Vogue posted on Instagram shortly after hearing about his garrulous, inquisitive friend’s demise from cancer. Nearly everything in the shop had a story attached to it, leading The New York Times to declare its owner a “provenance fetishist.” Gibbs happily concurred, saying, “I like intrinsically beautiful things, but if there's a yarn attached, that's a big plus.” Wear and tear was welcomed, even preferred: gilding worn to the quick, carpets closing in on the threadbare. “I like things in their natural state—people especially,” Gibbs told Mason. “Objects and people that are unmonkeyed with, that are themselves, not trying to be something else.”

The shop, to howls of protest, closed more than a decade ago,

after Gibbs decided to move permanently to Tangier, as much

because of his advancing age as for changes in popular taste,

which he politely decried. Collectors today “want a good car, a

good sound system, and a huge pink heart painted by Damien Hirst

with dying butterflies on it which costs £400,000,” he said,

plainly puzzled. “Yet for much less you could buy something

completely fascinating made 300 years ago.”

House &

Garden - Unforgettable advice from the late, great antiques dealer

& aesthete Christopher Gibbs, who died on Sunday

House &

Garden - Unforgettable advice from the late, great antiques dealer

& aesthete Christopher Gibbs, who died on Sunday

Described by the Telegraph as ‘the great civilising

influence of the high 1960s counterculture,’ tributes have been

pouring in for the late collector, antiques dealer, bibliophile

and tastemaker Christopher Gibbs, who died yesterday in Tangier.

Expelled from Eton for conning the local antiquarian bookseller

into buying back its own stock, Gibbs set up his first antiques

shop in Islington just as Sixties London was beginning to swing.

Forming part of a group of socialites, fashion designers and

flamboyant pop stars, who are now the stuff of cultural legend,

his set, which included the Rolling Stones, re-invented the idea

of dandyism, and made the English home cool again.

Described by the Telegraph as ‘the great civilising

influence of the high 1960s counterculture,’ tributes have been

pouring in for the late collector, antiques dealer, bibliophile

and tastemaker Christopher Gibbs, who died yesterday in Tangier.

Expelled from Eton for conning the local antiquarian bookseller

into buying back its own stock, Gibbs set up his first antiques

shop in Islington just as Sixties London was beginning to swing.

Forming part of a group of socialites, fashion designers and

flamboyant pop stars, who are now the stuff of cultural legend,

his set, which included the Rolling Stones, re-invented the idea

of dandyism, and made the English home cool again.

His work was beautifully defined by Christopher Manson in a 1990’s

profile in the New York Times; ‘He is the leading proponent of

that that elusive brand of anti-decoration, high-bohemian taste

favoured by self-confident Englishmen, a look based on well-worn

grandeur, disarming charm and unexpected contrasts.’ In tribute

we’ve unearthed our favourite Christopher Gibbs quotes. Timeless

advice which will stand for generations to come.

"We have got to the extraordinary moment when everything is

held to have a value, 'I'm a great chucker-out. I go into

people's homes and say: 'Chuck it out, chuck it out'. They say:

'But I won't have anything to sit on'. I say: 'Sit on the floor,

then, until you find the right thing'.'

'As life goes by, that's what I admire. Objects and people

that are unmonkeyed with, that are themselves, not trying to be

something else.'

‘Following your nose. Finding out who the best merchant

is. Sleuthing round sale rooms. Then only buy the things you're

really turned on by.’

'I love to bring light into gloom. Even dark-panelled rooms

can come leaping into life with the help of Chinese

blue-and-white ceramics or a refreshing Meissen sculpture.'

'I try to find things for my clients which I have never

seen before, which they have never seen before and which neither

of us are likely to see again. I might see beauty in strange

things, strange beings, strange places.'

Most old stuff is rubbish. And lots of it is hideous. But

if you want to buy a nice table or desk, it's only a few hundred

pounds - not more than a thousand.'

'They all want to be like everyone else. They want a good

car, a good sound system and a huge pink heart painted by

Damien Hirst with dying butterflies on it which costs

£400,000. Yet for much less you could buy something completely

fascinating made 300 years ago.'

The New

York Times - Christopher Gibbs, Avatar of ‘Swinging London,’ Dies

at 80

The New

York Times - Christopher Gibbs, Avatar of ‘Swinging London,’ Dies

at 80

Christopher Gibbs, the antiques dealer,

interior designer and fashion avatar, at his London home in an

undated photo. He helped establish the “distressed bohemian”

aesthetic.

Christopher Gibbs, an erudite London antiques dealer and dandy

who introduced the raffish “distressed bohemian” style to interior

design and helped start the Peacock Revolution in men’s wear, died

early Sunday at his home in Tangier, Morocco. Only minutes

earlier, at midnight, he had turned 80.

Cosimo Sesti, an architect and Mr. Gibbs’s godson, said in a

telephone interview from Tangier that the cause was respiratory

and cardiac failure.

Said to be a descendant of Margaret Pole, the executed

16th-century Plantagenet heiress to the English throne, Mr. Gibbs

was an aristocratic lodestone for rock stars like Mick Jagger

(“I’m here to learn how to be a gentleman,” Mr. Jagger was quoted

as saying after visiting Mr. Gibbs at his home), John Paul Getty

Jr. (whom Mr. Gibbs persuaded to donate $40 million to the

National Gallery in London), the Beat Generation novelist William

S. Burroughs; and Prince Rupert zu Loewenstein of Bavaria, a

banker who became the Rolling Stones’ business manager. They were

all clients of his or guests at his salons.

Mr. Gibbs had a reliable formula for surviving as a society

stylemaker in the 1960s. As he confided to Paul Gorman in his book

“The Look: Adventures in Pop & Rock Fashion” (2001), “you had

to be monumentally narcissistic and have time on your hands, and

just about enough money to do it.”

But Mr. Gibbs had more going for him than that. Unlike many of

his decadent mates, Mr. Gibbs was wise, worldly and endowed with

both a work ethic and a refined if finicky taste that was

undiminished by his extensive experimentation with drugs or his

predilection for exotica, like a stuffed, two-headed lamb and a

collection of whips.

“He is also a leading proponent of that elusive brand of

anti-decoration, high-bohemian taste favored by self-confident

Englishmen, a look based on well-worn grandeur, disarming charm

and unexpected contrasts,” Christopher Mason wrote in The New York

Times in 2000.

“The magic,” he added, “is in the mix of masterpieces and

oddities — like an assemblage of refined and wild-card house

guests who mysteriously combine to create the ideal convivial

country-house weekend. The allergy here is to the banal, not to

dust.”

As Mr. Gibbs himself put it: “I like things in their natural state

— people especially. As life goes by, that’s what I admire:

objects and people that are unmonkeyed with, that are themselves,

not trying to be something else.”

In 1960s Swinging London, the people who aspired to the hedonistic

set were habitually trying to be like him.

As a clothes horse himself and also while editing the shopping

guide of the quarterly Men in Vogue magazine from 1965 to 1970,

Mr. Gibbs was credited with popularizing flared trousers, caftans

and print shirts.

His eclectic taste in objects leaned toward elegant mahogany and

marbled tables, shabby sofas, faded damasks and a sock cabinet

that was designed by Sir William Chambers and that belonged to the

first Earl of Iveagh (smelly socks included). Taste, he once

suggested, could not be taught.

Mr. Gibbs, right, with his friends Mick Jagger and Marianne

Faithfull in Dublin in 1967. Taste, he said, is “something you

catch, like measles or religion.”

“It’s something you catch,” he said, “like measles or religion.”

His objects of desire filled his Cheyne Walk home in London, which

was borrowed by Michelangelo Antonioni for the party scene in his

movie “Blow-up” (1966) and by Kenneth Anger to shoot the occult

film “Lucifer Rising” (1972).

Mr. Gibbs also designed what he called the “earthly paradise”

inhabited by the has-been rock star played by Mick Jagger in

Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg’s film “Performance” (1970).

“Christopher was almost single-handedly responsible for making

English antiques, and English heritage, look ‘cool’ again,” James

Reginato, writer-at-large for Vanity Fair, said in an email.

Mr. Gibbs’s London manor, which once belonged to the painter James

McNeill Whistler, was also the scene of a party for the poet Allen

Ginsberg, where the hors d’oeuvres included a batch of

industrial-strength hashish brownies. According a biography of Mr.

Jagger by Christopher Andersen, the socially active Princess

Margaret was among the guests who were hospitalized that night

with what was diagnosed as food poisoning.

Christopher Henry Gibbs was born on July 29, 1938, in Hatfield,

about 20 miles north of London, to Sir Geoffrey Cokayne Gibbs and

Helen Margaret (Leslie) Gibbs.

Even as a 14-year-old Etonian, he affected velvet slippers, a

monocle and a silver-topped cane with blue tassels. A year later,

he was expelled, as he later explained unapologetically, for

“illicit drinking, panty raids of other boys’ rooms — that sort of

thing.”

After studying, according to various biographies, at the Sorbonne

and the University of Poitiers in France and lasting three months

in the British army (he had polio as a child and was soon found to

be medically unfit), his mother in 1958 staked him to a goodly sum

(about $225,000 in today’s dollars) when he was 20 to open an

antiques dealership in Chelsea.

That same year he began making buying trips to Morocco to scope

out brass lamps, carpets and other merchandise for his store and

his clients.

Mr. Gibbs played hard, but worked hard, too.

“The only thing I’ll say in my favor,” he recalled, “is that I was

practically the only person I knew who actually went to work at

nine o’clock in the morning, whether I’d been up to eight o’clock

or not, because I had a job, my own business, and I realized that,

if I didn’t, I wouldn’t have any of those things.”

In 1972 he bought Davington Privy, a 12th-century former convent

in Kent. After his mother died in 1980, he also took over his

childhood home, the 19th-century manor house at Clifton Hampden in

Oxfordshire. He sold it in 2000 after his 90-year-old housekeeper,

Louise Wagland, the only other occupant, died.

He moved full time to Tangier in 2006, where he lived with his

partner, Peter Hinwood, who survives him. There he served as

warden at the Anglican Church and tended his orchard of

pomegranate trees and poisonous plants on a slope overlooking the

Strait of Gibraltar.

He admitted to sometimes getting “homesick for snowdrops,” but to

Milly de Cabrol, a New York interior designer who visited him in

2000, he had acquired the look of the very things he liked — of

someone in his “natural state” — as he surveyed the breathtaking

vista in his flowing caftan.

“He looked like Moses walking in the olive garden,” she said,

“very peaceful, and looking forward to spending more time there.”

EuroBishop -

Christopher Gibbs RIP

EuroBishop -

Christopher Gibbs RIP

Bishop David Hamid for the Church of England Diocese in Europe.

Christopher Gibbs, one time Churchwarden of St Andrew's Tangier, and a

key lay leader in the congregation for many years has died in the city

he loved just one day before his 80th birthday. He called Tangier a

“chimeric place”, presumably as it seems almost like a creature, pieced

together from so many cultures, peoples, and influences. A perfect place

for the antique collector Christopher to make his home. His funeral was

today in St Andrmythicalew's and he was buried in the churchyard.

Christopher Gibbs, one time Churchwarden of St Andrew's Tangier, and a

key lay leader in the congregation for many years has died in the city

he loved just one day before his 80th birthday. He called Tangier a

“chimeric place”, presumably as it seems almost like a creature, pieced

together from so many cultures, peoples, and influences. A perfect place

for the antique collector Christopher to make his home. His funeral was

today in St Andrmythicalew's and he was buried in the churchyard.

Known to many as a friend of rock stars and of many of the world's rich and famous, and even having been attributed with the invention of “swinging London”, Christopher's great love in latter years was the Church of St Andrew. He adored its quiet beauty inspired by Moorish tradition, and was proud that it was a gem which the great Matisse was moved to paint. Christopher loved the people of St Andrew's and had a particular generosity of heart towards the newest parishioners, the many from sub-Saharan Africa, who have made this Church their home and who find comfort and hope in this spiritual oasis. Christopher was deeply moved by the stories of those who have migrated here from lands to the south, and was impressed with the faith and dignity of St Andrew's African parishioners whom he described warmly as “chic, graceful and brave”. Despite a great distance in upbringing and culture, Christopher believed the truth that God calls us all to be one family, and thus he felt at home in St Andrew's with his African sisters and brothers.

As a Churchwarden for so many years, Christopher was a supporter and friend to the priests who have served here over the years. It is Christopher’s vision that has helped St Andrew’s move to its present phase of its life, after so many years of locum chaplains, but now served by a permanent resident priest. It was with Christopher's bold encouragement to me as bishop that I sought a priest for St Andrew's, Fr Dennis Obidiegwu, who would be able to relate to the diversity of the parish.

Tangier now mourns one of her beloved residents. St Andrew’s mourns the passing of a dear brother, friend and mentor. We entrust our companion in faith Christopher into the hands of our Lord Jesus Christ. May the angels and saints meet him, and lead him through the gate to life and eternal fellowship with God.