Antony Gibbs beginnings at Exwick’s Woollen Mill

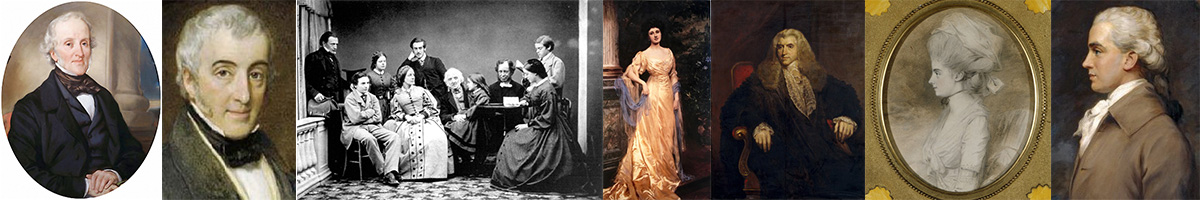

The painting of Antony Gibbs, a copy of which was fixed in the panel of the Court of the London Royal Exchange in 1927 in recognition of the firms banking prowess, has a background landscape view of the city of Exeter from the hill just behind Antony’s one-time house in Exwick.

The woollen mill in Exwick could be seen as the catalyst of Antony’s business venture, but also his ruin, driving him to Spain to seek his financial recovery. Having completed a 4-year apprenticeship with an Exeter merchant who was extending his Spanish branch, he started exporting woollens and was elected to the Guild of “Weavers, Fullers and Shearmen”. His aim was to save £1,000 of his own before he could marry his fiancé Dorothea Hucks.

The story of these early years in Antony’s career and his family relationships and friendships is well recounted in Chapter II of The History of Antony and Dorothea Gibbs, leading up to their marriage in 1784.

By early 1785 Antony and “Dolly” had moved to Exwick House, and there was set up wooden cloth factory in which he was apparently the senior partner of the firm Gibbs, Granger and Banfill.

I was intrigued to find to find an interesting account of this Exwick Wollen Mill on a website of Exeter Memories, the full full story of which is here.

Exwick’s largest and most extensive mill, was not built until 1786, after a young Antony Gibbs, a budding woollen merchant and son of George Abraham Gibbs, of Clyst St George had gone into partnership with the Exeter merchant Edmund Granger. Granger produced £10,000 for the new business, while George Abraham Gibbs pledged £5,000. Producing woollen serge (a high quality woven wooden fabric) had made Exeter a prosperous city during the late 17th and for most of the 18th Centuries, and Antony Gibbs wanted to emulate the successful Baring, Kennaway and Duntz merchant dynasties, who had become rich from wool.

Antony, with his brother Abraham, had been running a serge exporting business to Spain from 1778, and had spent time in the country, becoming fluent in the language. His brother had died in 1782 leaving him to run, with some concern from his father, the business alone. His friend, Samuel Banfill had spent a year in Spain drumming up business for him during 1783/4. Banfill would become the third partner in the new mill in 1787 and he became family when he married Anne Gibbs, Antony’s sister. With Granger acting as the accountant, and Banfill as the manager, Antony Gibbs purchased in 1785 the remaining 60 year lease on the Higher Fulling Mill, one of three wheels at Exwick Corn Mill, further up the leat, to full his cloth. It is not clear how long this mill remained fulling for the company, but by 1815, the wheel had reverted to driving stones to mill corn.

The estate of Exwick Barton came up for sale – the estate included Exwick Manor House of which the corner site of the Village Inn was part, various cottages and other buildings including the Hermitage on Exwick Hill, and some land straddling the leat below a fulling mill that was already working for John and Charles Baring; this mill is remembered by many as the old County Steam Laundry. The Barings ran their business from Larkbeare House in Holloway Street, where the workshops and warehouses devoted to dying and pressing of the fulled serge were located.

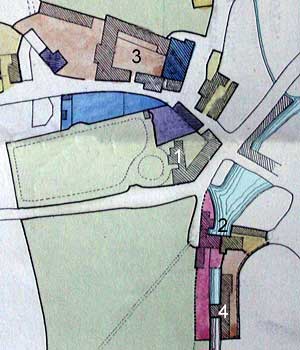

Antony purchased the house, land by the leat and other property in the village and built a new mill opposite the present site of the Village Inn. He had 31 elm trees cut down, several loads of stone and 3450 bricks delivered in 1786 for the new complex. The new mill drove spinning machines and other equipment to finish the cloth. Dye and washing houses were built next to the leat, on the site of the present Exe View Cottages. Counting houses, warehouses and weaving shops were constructed in the Square, Exwick Hill and on the site of Rackfield Cottages. Housing for the factory workers were also constructed on Exwick Hill.

By 1789, it was obvious that Antony Gibbs had over extended himself, borrowing from Granger, Banfill, his father, and others, and failing to pay many outstanding bills. His position was dire, and a letter in the Flying Post summed up his standing with one disgruntled, if poorly educated member of the local community:

“Jan. 12, 1787

Mr. Antony Gibbs i have took this opportunity in sending thes few lines as a frindly Caution Concerning many Destervence that have hapned Times past you Damnation Black Skandlous Dog now to be very Pecuhlor i Cant stop about it to your very Great Surprise you shall find your litle Pile of Buldings one Morning all in flams and not only your Buldings but you will find the Racks cut from end to end you Damnation Black Dog.

Excuse the writing.

To Mr. Antony Gibbs and Co. Merchants

Exweek Devon”

Gibbs, Granger and Banfill offered a reward of a £100 for the conviction of the offender responsible for the threat.

Trade for other Exeter merchants during the late 1780s was not good either, and there had been some failures of merchants in the city, as the French Revolution caused turmoil across the European markets. Things went from bad to worse when the banks refused Gibbs credit and he was declared bankrupt, owing £18,000, forcing him to leave the partnership. The true value of Gibbs’ debt at today’s value, measured against average earnings, is £20,800,000 – even when measured against the retail price index the loss was more than £1.7 million. His father, as a major investor, was also liable and in 1789, he was also bankrupted, for the even larger sum of £22,000.

It was decided that Antony would return to Madrid and act as the Banfill and Granger agent, with any earned commission going towards paying off his debts. Antony’ reckless business acumen and habit of extending easy credit to his customers saw little of his debt repaid.

By 1807, Antony Gibbs had returned to London with his family, still heavily indebted to his former partners. He founded the House of Gibbs, and died in 1815, aged 59. His son, William Gibbs would in the 1850s, make a success of the business with the importation of guano for use as a fertiliser, and it was through bird droppings that William Gibbs, a conscientious and pious individual, eventually paid off his father’s debts. He became the wealthiest businessman in England, and purchased Tyntesfield, near Bristol, now a National Trust property. He would also use some of his wealth building St Michael’s Church, Mount Dinham and extending Exwick Church.

Antony Gibbs’ brother Vicary was a successful lawyer who would become Attorney General between 1807 and 1812. He purchased the estate from the company and leased the woollen mill back to Banfill and Granger, while at the same time, selling Exwick Barton to the Rev. Duke Yonge of Pulsnich. Samuel Banfill moved into Exwick Manor House to run the mill free of Antony Gibbs, and the business survived through difficult times, as the French market was lost.

The article goes on to recount the further history of the mill, based on reports in “The Flying Pig”. A disastrous fire occurred at the serge and flax mills in 1861, and it was completely destroyed by a huge blaze on Saturday 17th April 1869. Nothing now remains of a mill complex that some compared with the large industrial mill towns of Lancashire.

Thank you for this latest post; and for all the past and (I hope) future posts. I particularly enjoyed the sketch of HMG in Letters home from the Peruvian Sierra.