Henry Martin Gibbs – Letters home from the Peruvian Sierra

An expat recently went on a hunt in the Peruvian Andes for clues about a couple of Victorian Englishmen who went to the area in the 1870s, and were decent enough to write home about it – more than 80 of these letters have been kept by the family!

“An Englishman abroad” Letters home from the Peruvian Sierra 1873 – the full story can be found here.

On October 13th 1873 a boat set sail from Liverpool destined for the port of Callao, Lima, a journey of upwards of fifty days, stopping at various illustrious ports. This particular boat, the Chimborazo, was carrying a passenger named Arthur Malcolm Heathcote, accompanied by his friend Henry Martin Gibbs, youngest son of William Gibbs of Tyntesfield, who had been advised to spend some time in the clear air of the Peruvian Sierra to recover from a lung complaint.

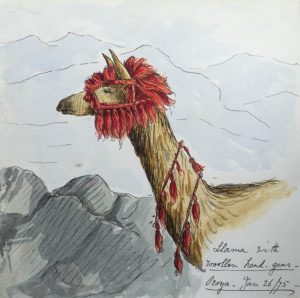

After a short stop at Valparaiso and a trip up to Santiago and Cauquenes in the Chilean Andes, they arrived in Callao aboard another ship, the Cordillera, on 19th December. Arthur Heathcote did not have much to say about Lima, as he was probably preparing for the daunting journey up into the Andes. There were mules to be bought and guides and arrieros (muleteers) to be found. A journey that today takes 4 or 5 hours in a car took for them 9 days by train and mule.

The intention was to stay in a town at the head of the Mantaro valley called Jauja, but after a month they decided that town life was not to their taste, and they looked to move to a small village down the valley named Matahuasi. There, they were able to enjoy the benefits of living quarters containing “more rooms than we have here, two patios, a good corral, and 2 gardens or orchards, one large and one small”.

Aside from one lengthy but spectacular sojourn over the mountains and down towards the jungle, they were to spend the rest of their time in the sierra in Matahuasi, and the majority of the letters describe their day-to-day life there, relations with the staff, dealing with an unfamiliar culture and, perhaps more amusingly, the ways in which they brought their own culture to Peru!

What strikes one most about the letters is how quintessentially “English” they are. The daily routine is telling!

“From nine to half-past nine we do either Latin or Greek together and from half-past ten to one is our time for exercise, whether walking or riding out… at 2.30 we have a space for reading the papers; Gibbs gets the Guardian and Saturday Review. Then we have an hour’s Spanish and an hour’s history and then spend half an hour pacing up and down our verandah learning by heart either Latin or Shakespeare. From then till dinner is time for letter writing”.

They seem to have taken an interest in the local culture, with frequent visits to the local “big smoke”, Huancayo and other villages thereabouts to check out and buy local vicuña textiles at the Sunday morning markets. Interested in the local culture as they were, Heathcote drew the line at bull-fighting. Matahuasi still has its bull-ring, and Heathcote does make comment: “As practised here, this barbarous amusement is truly sickening”

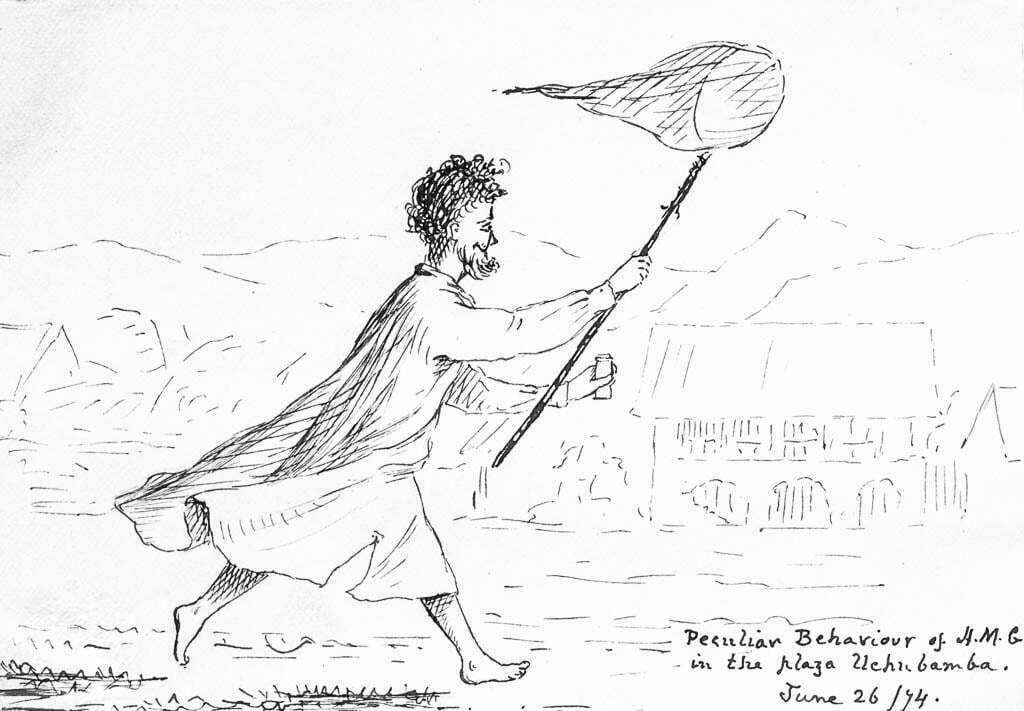

Regarding English eccentricities, aside from the butterfly catching and shooting expeditions, it is likely that Heathcote and Gibbs’ most startling pastime to the local population was their love of amateur dramatics. In their audiences they included not only friends but also the household staff. Their first evening of entertainment, complete with painted scenery, theatrical wardrobe and lighting “was an eminent success and puzzled them all tremendously, indeed one of the sisters was quite frightened at first.”

From the letters, it would seem that the two of them spent most of the rest of their time in Matahuasi putting on plays. Once the news spread to the surrounding area of their success; “quite nice little party, and all enchanted. They had never seen anything of the kind, and the scenery, the dresses and the dancing quite transported them”, they seem to have struggled to keep people from the door! “We found it necessary to keep the front gates locked for there was quite a crowd clamouring for admission”.

But even at this stage, they were missing the piece de resistance. They had ordered a piano to be brought up from Lima by mule to add a final touch to the performances. It eventually arrived about two months before they were due to leave.

“The evening was most enlivened by the piano. Doña Jesusa can play, although it is with a hand of iron and a touch of wood, but knows more things than we expected… afterwards we cleared the room with a view to some dancing and managed a mazurka very fairly, though Doña Jesusa’s time was fearful!”

Despite the health problems cited as the reason for the trip to Peru, Henry Martin would go on to become High Sheriff of Somerset and live to nearly 78. He arrived back in England a few days after the death of his father, William Gibbs, who had been involved with Sir William Heathcote in the Oxford Movement and plans to create Keble College. With his elder brother Antony he participated in the opening service for Keble College Chapel and they provided funds for further buildings at the college. He was also a significant benefactor of Lancing School, where there is now a house named after him.

Pingback:Charlotte Mary Yonge – novelist of the Oxford Movement – Gibbs Family Tree