Trees and my Gibbs Roots

Contributed by my cousin Sarah Gibbs

It all started with a Poem and a Tyntesfield Oak

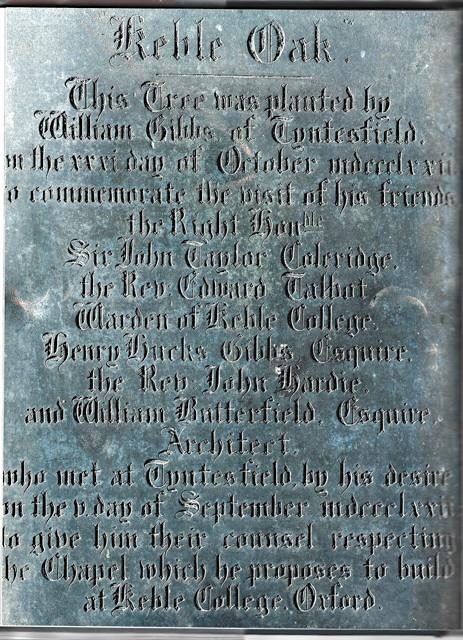

Some of you may remember the Post ‘Poem for a Tyntesfield Oak Tree’. I had come across a poem ‘Inscription for an Oak Tree’ whilst sorting through books and papers cleared from my father Denis Gibbs’s study. The poem was written by Sir John Coleridge as an inscription for an Oak Tree that William Gibbs planted at Tyntesfield in 1872 to commemorate plans for a Chapel at Keble College, Oxford, for which William offered to fund the building.

Since the time of discovering this beautifully scripted poem in 2018, I had longed to combine my love of trees with the joy of hunting down the Keble Oak (and other trees) at Tyntesfield. After all, with trees, there is always an opportunity for connection. And what better way to connect with and get to know my Gibbs ancestors of the 19th century than to see, feel, touch and hug the trees at Tyntesfield.

Hugging the Tyntesfield ‘Keble’ Oak and other Tyntesfield Trees

So, on Saturday 24 May 2025, my friend Jillian Spencer and I were taken on a very special Tyntesfield Arboretum tour by Liz Buckingham, Estates Guide, through Paradise itself (the Gibbs family name for the Arboretum). The final delight was the glorious Keble Oak. We were joined by David Hogg, supporter of the National Trust and Tyntesfield. William Gibbs bought Tyntesfield in 1844 and, since then, four generations of the family have planted ornamental trees from all around the world. The wealthy middle classes of the late 18th century took a keen interest in importing and planting exotic (non-native) trees, and plant hunters were sent across the globe to seek out new specimens. The Paradise garden at Tyntesfield is an example of a Victorian arboretum, a showcase for specimen trees.

As Liz started our tour, I was overwhelmed by the beauty and variety of the trees around us. Liz must have shown us around 20 trees. I will mention just a few of my favourites here.

The Weeping Ash

One of our first stop offs was the Weeping Ash. Ash is native to the UK, and was widely planted in the Victorian Era. The original tree was small, so taller specimens were grafted high up to produce a tree with a tall trunk and upper pendulous branches. Ash is dioecious, meaning that male and female flowers typically grow on different trees, although sometimes a single Ash tree can have male and female flowers on different

branches

Why do I like this tree so much? : As the Tree parts and then grows into one trunk again further up, a heart shape emerges. For me a symbol of love and close family ties.

The Silver Lime

The Silver Lime, pictured here with Liz, is a beautiful and elegant tree. It was introduced to the UK from SE Europe in 1767 and gets its common name from the hairy, white undersides of the dark green leaves.

Why do I like this tree so much? : The leaves say it all – perfectly shaped, abundantly formed, and with a shiny exterior and paler underside. I thought about how we can all put on a brave face whilst sometimes feeling fragile inside.

The Camperdown Elm

The Camperdown Elm brought a smile to my face. With an unusual and perfectly formed exterior shape, as we stepped underneath this small and tight-leaved tree, the twisting shape of its trunk and branches reached up and out in all directions creating a perfect canopy of leaves from which to shelter from the elements. Around 1840, the gardener of the Earl of Camperdown in Scotland found a small, contorted elm tree in the forest. He replanted it in the Earl’s Garden at Camperdown House in Dundee, where it remains. He grafted cuttings onto Wych Elm root stock making a popular tree that was widely distributed.

Why do I like this tree so much? : The tree is small in comparison with its neighbours and yet just stepping underneath its canopy reveals a beautiful and unexpected interior.

Trees, like humans, value their uniqueness.

The Oriental Plane

The majesty and scope of this Oriental Plane tree says it all. Native to Turkey, SE Europe and India, it was introduced to the UK in 1550. The Tree of Hippocrates, under which Hippocrates gave his lessons on Medicine on the island of Kos, was reputed to be an Oriental Plane.

Why do I like this tree so much? : My father, Dr Denis Gibbs, entered a travel writing competition for the BMA News Review in 1989. He submitted an entry on Kos and the ancient site of Knidos. As I hugged this tree, memories and joys of my father came flooding back, as did my love for Greece.

The Keble Oak

I hug this tree with delight as I finally meet and witness the tree that symbolises the meeting of, at the request of William Gibbs, five of his friends on 31 October 1872 at Tyntesfield to discuss plans to build the Chapel at Keble College. We found the plaque too that used to sit in front of the tree (now safely displayed in the House near to Tyntesfield Chapel) and that was the foundation for the Poem: Poem for a Tyntesfield Oak Tree, that I had found in my father’s study a few years ago

Why do I like this tree so much? : The Poem had led me to this wonderful day of immersion into the Trees at Tyntesfield’s Paradise Arboretum.

Has my day with the Tyntesfield Trees brought me closer to my Gibbs roots?

Most definitely. In Sarah Spencer’s book ‘Think Like A Tree’ she says that ‘trees can remember, and can even pass memories between generations’. So here are some of the ways that the Trees at Tyntesfield have helped me to feel closer to my Gibbs roots and to re-kindle family memories:

Faith and wisdom: trees and woodlands grow and operate with incredible faith and wisdom. As Sarah Spencer says ‘trees possess the ability to know what they are supposed to be doing, and how to do it in the most effective way possible’. William Gibbs and his wife Blanche and many of my Gibbs ancestors were devout and committed Christians, demonstrating their ‘knowing’ and faith by helping and supporting educational, religious and charitable institutions, by creating welcoming communities for all (the Tyntesfield estate) and by acknowledging the importance of family. It reminds me of my grandfather, Michael McClausland Gibbs, Dean of Chester Cathedral 1954-1962, such a wise, kind and dedicated man. ‘Much of his time was devoted to spiritual counsel and direction, individually through retreats, and helping others in need’.

The magic of family: In Simon Barnes’s book ‘Rewild Yourself’ he talks about the ‘magic of trees’. He writes that ‘all trees have some kind of magic about them: huge things that start as an object you can hold between finger and thumb, living things that are also life- givers, offering food and shelter to all-comers. I equate the magic of trees to the magic of the Gibbs family and being a member of it. Thanks to the Gibbs Pedigree – the first was brought out in 1890 and was edited by Henry Hucks Gibbs, William Gibbs’s nephew; the fourth was edited by my mother, Rachel Gibbs; and now this online Gibbs Family Tree is administered by my first cousin, Michael Gibbs – I can date my ancestry right back to the 14th century. I know exactly where I come from, I know my heritage in great detail, and I have a living family of cousins far and wide – first, second, third, and ‘removed’ – whether from A stream, B stream or C stream (Gibbs family will know!) – who come together in their hoards sporadically to attend Gibbs Family parties (we had one at Tyntesfield in 2013). This is Gibbs family magic.

Innovation: The trees at Tyntesfield can be considered innovative because they showcase a unique collection of trees from around the world, including many champion trees. It was William Gibbs’s passion for all things innovative in nature that helped to create the Tyntesfield arboretum called Paradise. ‘It was the golden era of plant collecting and resulted in Victorian gardeners having an amazing range of new plants to add colour, shape and height to their gardens and landscapes’ (Tyntesfield, National Trust). Indeed, some of the Cedar Trees at Tyntesfield are grown from seeds brought back from the Holy Land in 1858. I am reminded of the Cedar Tree of Lebanon in the churchyard at Clifton Hampton, Oxfordshire under which my father’s ashes are buried. An innovative man himself, he was one of the first Gastroenterologists to use an Endoscopic camera.

Roots, caring and growth: Peter Wohlleben states in The Hidden Life of Trees that ‘the root is certainly a more decisive factor than what is growing above ground. After all, it is the root that looks after the survival of an organism’. I think of the millions of tree roots there must be under the ground at the Tyntesfield Estate, supporting, caring for and looking out for each other. As Peter says ‘trees converse via fungi that connect their roots like fibre-optic internet cables’. Four generations of the Gibbs family planted trees in the parkland at Tyntesfield, continuing the family’s devotion to nature and the environment – ‘the age and variety of Tyntesfield’s parkland trees add significantly to the biodiversity of the estate today’ (Tyntesfield, National Trust). These trees and their roots are symbolic indeed of the growth and caring of the Gibbs as a close-knit Christian family who have stories (to name of few) of exploration, adventure, merchant trading, banking, politics, religion, and even bankruptcy and shipwreck. It is the Gibbs roots that have helped them to feel ‘connected and grounded’ as times change. As Sarah Spencer says ‘strong roots anchor us and allow us to ‘dig deep’ when times are tough’.

Connection: ‘Everything is in some way connected to everything else’ (Leonardo da Vinci). I like to think that my great-great-great-great Uncle, William Gibbs of Tyntesfield’ was aware of this too. And that through his vision for the trees, gardens and parklands at Tyntesfield that he himself was acting as a connector for family, friends, his estate workers, his beneficiaries, the community, and also further afield within his Christian faith, his support and generosity within the Tractarian Movement, and his philanthropic activities. I have a strong sense of family connection too and, as I hugged the Keble Oak at Tyntesfield, I was reminded of the 365 different trees that I hugged – one for each day of the year – in 2017 in memory of my father, Dr Denis Gibbs.

So, a big thank you to the Keble Oak, to all of the other trees at Tyntesfield, and to Liz Buckingham and David Hogg for making it all happen and to my wonderful friend Jill for being there with me and for taking the photos. Thank you for reminding me of the magic of being part of the Gibbs family and for my strong family roots.

Thank you

I see the family resemblance !

Trees are in the DNA , Gibbs & pytt/ Pitt/ Pitts all had a history in planting many trees for building ships , for commerce , defence, & piracy , so where do I start , 1575 William pytt – Mary Gibbs Bristol Tomas Pitt Alderman D: 1613 , brothers Christopher, Edward, QE1 Armada , 1585 , Thomas Dimond Pitt governor fort St George B: 1654, trees at stratfieldsay, Gibbs bay Barbados 1645 , slave trade Bristol inquired why 10,000 boy and maidens shipped to the colony’s , myself 1000 trees and still planting