Christopher, His World, the Book and Tangier

This past month of May has been an opportunity and delight to become absorbed in the world of Christopher Henry Gibbs, and share the experience with much of my close family.

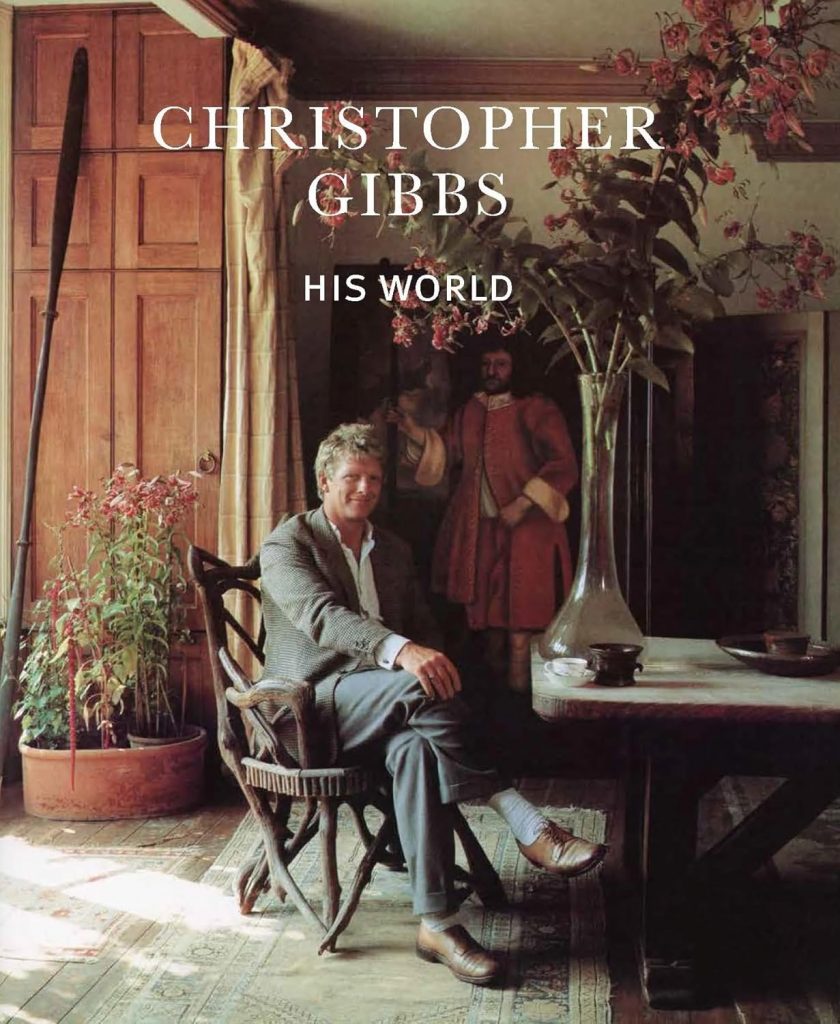

The month started with the launch of Lucy Gibbs’s (née Moore) fabulous book about Christopher, held at Christies in London, surrounded by many relatives, friends and associates. The book is full of photos and stories through the phases of his life, from growing up in Hertfordshire, getting expelled from Eton, seeking adventure and discovering Morocco, his wild social life, through to becoming the icon of fashion, style and antiques and decor. Much of it draws from Christopher’s personal notes, letters and articles he wrote for Vogue and other prestigious magazines.

Christopher was also passionate about his family origins and history, and in this context I was fortunate to spend some time with him when compiling this website, of which he was very supportive.

Lucy Moore wrote:

‘Antiques dealer, interior designer, aesthete, socialite and tastemaker extraordinaire, Christopher Gibbs pioneered a style of interior decoration often described as “distressed bohemian” – a mixture of refinement, exoticism and well-worn grandeur. This book charts his life story through his own diaries and magazine articles from Chelsea and the Rolling Stones in the 1960s to El Foolk, his house in Tangier in the 2010s.’

‘Taste is difficult to define, but Christopher’s is absolute perfection.’ Min Hogg, World of Interiors

More about the book, and Lucy’s other works, at https://www.lucymoorebooks.co.uk/christopher-gibbs

Christopher Gibbs (1938-2018) was an antique dealer, collector and tastemaker, often credited with shaping the aesthetic of ‘haute bohemian’ style and whose circle of friends defined the Swinging Sixties. He created beautiful houses and gardens in London, the English countryside and, most famously, in Tangier. Lavishly illustrated, using his writings as a chronological guide and working closely with the Gibbs family, in CHRISTOPHER GIBBS: HIS WORLD Lucy Moore documents his life, his work, his love of family and his gift for friendship.

‘I first came to Tangier in the spring of 1958 … I’d been in Essaouira, Marrakech and Fez … We arrived at last in Tangier, putting up at the Hotel Rembrandt … We found a small, shabby town where most of the citizens wore native dress, animals roamed freely, green hills or sparkling seas closed most views and everywhere was the sound of music, flute, drum and the twanging raita … or I’d hang out with Bill Burroughs and Brion Gyson...’

Tangier has a fascinating history, with some similarities to Cadiz and Gibraltar in Southern Spain, only 14 kilometres across the mouth of the Mediterranean and clearly visible. A strategic Phoenician town in 10th century BCE, then Greek, becoming Roman with the Punic Wars, Byzantine, Muslim under the Umayyads who went on to conquer most of Spain. Captured by the Portuguese in 15th C, passing to Spanish control in 17th C, it was given to England in 1661 and fortified but constantly under attach from mujahideen fighting a holy war until Morocco occupied the city from 1684. From the 18th century, Tangier served as Morocco’s diplomatic headquarters, and was the first place to recognise United States independence and its first consulate.

19th C saw colonial jockeying and conflicts leading to most of Morocco becoming a French Protectorate in 1912, except for the Tangier International Zone created under the joint administration of France, Spain and United Kingdom in 1923, ‘a cosmopolitan society where Muslims, Christians, and Jews lived together with reciprocal respect and tolerance, where men and women, with many different political and ideological tendencies, found refuge, including Spaniards from the right or from the left, Jews fleeing Nazi Germany and Moroccan dissidents‘. Tangier joined the rest of Morocco in 1956, at which time it had a population of around 40,000 Muslims; 31,000 Christians; and 15,000 Jews.

This liberal period, and for some time after, gave Tangier a unique draw for numerous European and American writers, musicians and artists seeking escape from constraints at home; Paul Bowles, William Burroughs, Brion Gysin, Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, Tennessee Williams, Truman Capote, Brian Jones, Mike Jagger and Keith Richards, Henri Matisse, Francis Bacon, Claudio Bravo, Marguerite and James McBey to name a few …

Christopher developed a love for Tangier and decided to make it his main home; in 2000 he sold The Manor House in Clifton Hampden, near Oxford, which had been in the family since 1726. He bought the McBey’s house on the Old Mountain, expanding into neighbouring properties, reconstructing the ruined chapelle, adding a pool and hammam, surrounded by sumptuous gardens with breathtaking views of Tangier city and across the Straits of Gibraltar to the coast of Southern Spain.

He embraced the role of Church Warden at St Andrews, the historic Anglican church within Tangier, built on land given to the British community in 1880 by the Moroccan king.

The church blends arabic and european architecture and has been a haven for the British Anglicans as well as for numerous transiting migrants seeking a better life.

Christopher is buried within the gardens of this church. We were advised that whenever any Gibbses attend a service there (which we did) that one of them is expected to read a sermon.

Since Christopher’s death, the house and staff have been retained, and later in May I was very privileged to be able to stay there for a week, with the pretext of my impending 70th, joined by all 3 of my siblings, partners and most of the next generation. Tangier has grown into a clean modern city with well over a million inhabitants, yet ‘El Foolk’ remains an oasis of tranquility imbibed with Christopher’s style and mementoes. A truly memorable week for all of us.

So much history and fascinating places for us to explore. Up in the ‘rock da’ kasbah (castle) a museum was dedicated to Ibn Battuta, born in Tangier in 1304, explorer and scholar who travelled more than any other explorer in pre-modern history and dictated an account of his journeys through Africa, Middle East and Asia.

Walking up the hill past the walls and guards of the king’s family palaces, we came to the large public Perdicaris Park containing his castle mansion the ‘Place of Nightingales’. A wealthy Greek American, while in London Ion Perdicaris met and ran off with Ellen Varley, a married woman with four children, the great-great-grandmother of Jo Aldenham (Gibbs)! They travelled to Gibraltar and Morocco in 1876, and became significant players in Tangier community. His kidnap from the Place of Nightingales led to the Perdicaris affair with the USA sending the South Atlantic Squadron to threaten Morocco.

Christopher wrote an article on ‘Tangerine Life’ for Vogue is 1979, which sums up beautifully his feeling for the city:

Where Islam touches Christendom and Africa nods to Europe and the Atlantic roars over lost Atlantis into the calmer waters of the Mediterranean… there among green and wooded hills and distant blue mountains, among rocky outcrops and pale gold sands that seems to stretch forever, sprawls the ancient city and port of Tangier. Druid astronomers, conquering Romans, Phoenician and Carthaginian traders, Berbers, Jews and Arabs. Christians from Portugal, Spain, England and France have left their mark on her. On the high white point of the Kasbah was the sanctuary of Astarte, the moon goddess, and on the summit of the Charf, a mile along the Mediterranean coast, Hercules manhandled the giant Antaeus.

When Charles II married Catherine of Braganza in 1661, Tangier was her dot and Samuel Pepys was sent to sort the place out (Mrs James Wylie lives under Pepys’s fig tree, has Roman plumbing and make delicious jam; he is the delightful doyen of the English community). Sir Richard Burton who had ranged and plumbed the Moslem world only wanted to be her Majesty’s Consul at Tangier; she gave him Trieste. Lord Bute early this century succumbed to the fascination and bought and developed the modern centre of the town. Now the Moors have it back. Matisse came to paint here. So did Delacroix who felt he had stepped off the boat and into the ancient world. A few months in Morocco gave him a life’s work of imagery. Francis Bacon came too and gave carousal a new dimension at Peter Pollock’s Pergola Bar down on the beach. The grey shadow of William Burroughs stalked the Tangerine streets for a decade. Timothy Leary came for the summer. But some came for good.

Cut off from Christian culture and the Industrial Revolution until the last years of the nineteenth century, Morocco, with all the splendours of its courts and its ancient mosques and madrassas, and the dog poverty, and savagery of its subjects, became the stuff of fables. Sorcery, sodomy, and Long John Silvery was the legend. But Tangier was spasmodically open for trade with the Nasranis (as the Moors call those who do not follow the teachings of the Prophet). Its close proximity to Spain, its convenience as a port, and the continued presence of small Christian and Jewish communities made it the sole gateway by which the infidel might approach the secret fiefs of the Allaouite Kings, the haunts of the Barbary pirates and the remoter terrain of the warlords of Atlas. The glories of ancient Fez and Marrakesh, tile-paved courtyards, fountain-splashed and jasmine-scented, have their echoes in Tangier; which is still very much a Moorish city, with its fortified Kasbah enclosing the Royal Palace splendid sited at the top of the cliffs looking across to Europe; and with the walled Medina below almost encircling it. The streets in both Kasbah and Medina are narrow and sometimes unpaved, the houses tall and lime-washed, crowded with children at play. Shops are mostly in the lower part of the Medina off the street leading from the Gran Socco, outside the walls, with its markets and bus station, down into the heart of the Medina, le Petit Socco, the small square, all cafes, where sit and sin the more indolent and playful Tangerines.

Tangier, with by far the largest foreign community, also has a gentler, more antique, more rural quality than other Moorish cities: In the houses without the walls of the Medina, hanging on the cliffs of the Marshan, hidden in their gardens on the slopes of the mountain, or in handsome nineteenth-century villas with their iron gates and tumbling bougainvillea, along and behind the streets and boulevards of the older urban spread, a line remote from the whirling mill of Islam goes on. Here the price of Muscat grapes in the market on the rue de Fez, that vagaries of the new one-way traffic system, the fêtes of Señor de Velasco or Monsieur Vidal are matters of more moment than the antics of Jimmy Carter or the perfidy of the Union. Gentlemen play boule with their servants; ladies play bridge with each other.

It is the Moors themselves who beguile those who come to live in Tangier. Their grace and courtesy charm and soften, their vigour and their warm blood delight, their black-smouldering eyes enslave. Their very different temperaments and taboos revel gaps that exasperate in the bridge between East and West, but the intermittently enslaved who live in their English gardens on the mountain or their little Moorish houses in the Medina or their less architecturally appealing but sometimes more comfortable apartments off the Boulevard, are intermittently blind, like all lovers. They are the adepts of a ritual social dance that entirely disregards the indigenes. While the pulse of Islam throbs through them, their luncheons, cocktails and dinner parties tinkle on and the talk is of the PDSAs animal cemetery, the Dramatic Society’s Christmas pantomime, the summer festival of flowers in St. Andrew’s Church. There are of course Nasranis who are in Tangier due to the accident of birth or inheritance, in chief the Spanish, the French and the Jews, and it is with them that the English commingle rather than with the Moors. This leavening from oute mer transforms the Anglo-Saxon social round. Neither the food nor the company nor the conversation are quite what goes on in Sunningdale or Somerset.

The Tangier beaches, for dwellers from the frozen North, are a delight and a revelation. The Avenue d’Espagne, with its rows of palm trees, curves around the bay beside the railway, from the port towards the Malabata lighthouse. Cross the railway, dodging the elegant cream-painted streamlined trains that shun to and fro, and you will find half a mile of beach cafes, each with its cabins for bathers and sun worshippers to change in, its bar, its restaurant, and its gardens , open from Spring to Autumn, fronting the level sands that meet the sea one hundred yards away. The bay is sheltered and clean and on fair days one can swim for mile sin unruffled water lazily watching the football matches ashore; the boats sea; or imagining what is happening up in the little white villages on the hills. There is a string of rafts with diving boards a quarter on a mile offshore and, on the beach among the dignified and veiled Morrish ladies and the flower of Moroccan youth. I have seen a lady with a beard like W.G.Grace, toasting in the sun. For the adventurous there are the vast virginal beaches of the Atlantic coast with their foaming breakers, glaring sunshine and empty sands. Near the Cap Sparkle lighthouse there are caves in which to shelter but beware of sun stroke, of treacherous undertows and importunate Musclemen. For the shy paler-skinned, timorous lovers of solitude there are countless coves along the Mediterranean coast towards Ceuta, where one is unlikely to meet anything more fearsome than a few village ladies bundled up in stripy rags, hidden beneath the wide brim hats of straw, gathering cuttlefish.

As evening comes and the crowns and fountains of lights that arch over the boulevard begin to twinkle, all Tangier strolls the streets or sits on the terraces of the cafes drinking mint tea. It is the hour for dalliance and the air is warm and scented. The night falls and if you are not bidden to some Nasrani revels, it’s Lily’s Parade Bar, archetypal and delightful expatriate retreat, drinking within and tasty food in a leafy garden, or Raschid’s Nautilus down the hill, or Guita’s, up the hill with a bigger garden, or Le Claridge on the boulevard with the best food, or the splendid oasis of the Hotel Minzah, where the seamier delights of Tangier, elsewhere too insistent, seem far removed.

Comments

Christopher, His World, the Book and Tangier — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>