Clifton Hampden and a Gibbs Grave Story

The church of St Michael and All Angels at Clifton Hampden in Oxfordshire exists in its present form because of the Gibbs family – and it is an architectural gem. Pevsner talks of its “theatrical quality” standing on its cliff overlooking the River Thames.

The church is of interest in architectural history, Gibbs history and ecclesiastical history as an early product of the Oxford Movement. Joseph Gibbs, the vicar in the 1830s who was concerned about the decline in church life, persuaded his rich elder brother, George Henry, that the church needed redesigning in order to encourage people to participate. They appointed the young architect George Gilbert Scott, who created a masterpiece. He went on to design the Albert Memorial and St Pancras Hotel. “We have had little to restore – it is rather a refoundation”, he wrote when working at Clifton Hampden; it is a fine early Tractarian building. The screen with St Michael at the top surrounded by his angels is particularly important (a miniature version of those of Hereford Cathedral (now in the Victoria and Albert Museum) and Lichfield Cathedral).

The family was responsible for much other building in the village including the Manor (built first as the Vicarage), the bridge with its toll house, the school and the village hall. Whilst houses, school, river and bridge are all attractive, the building that binds it all together and makes the village special is the church. Jerome K. Jerome in Three Men in a Boat described Clifton Hampden as “a wonderfully pretty village”.

The church is now in a critical state; the roof is in urgent need of replacing. It was last recovered approximately 60 years ago and has reached the end of its life. Replacing the stone slates makes this a very expensive project. We are planning to carry out a number of other pieces of restoration and improvement as part of the project: repairs to stained glass windows and stonework; repair of a now dangerous flight of steps in the churchyard; improvement of access through the churchyard for people with a disability through a new paved pathway.

There are two items particularly associated with the Gibbs family: Christopher Gibbs in the last years of his life was very keen to create an attractive paved area with memorials to those whose ashes are strewn in the graveyard, which has little further space for burials; the memorial to Henry Hucks, the first Lord Aldenham, is in need of repair; and the grave of George Henry and Caroline and their family is in need of restoration.

A Family Grave and the Story it Tells

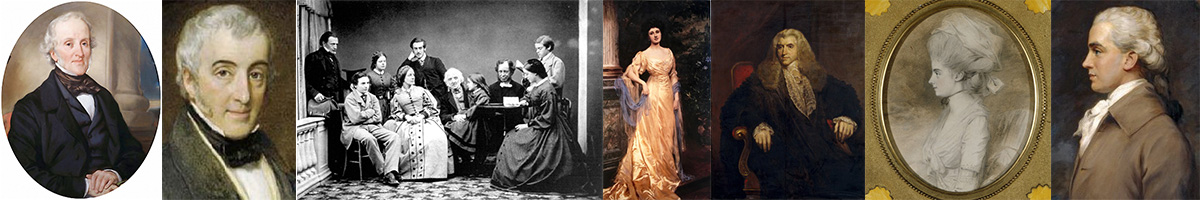

There is a grave in Clifton Hampden churchyard, next door to the east end of the church, that is much larger than all the others. There are no fewer than nine people buried in it, George Henry and Caroline Gibbs, six of their children and one grandchild. And this was only part of the family; they had had a total of fourteen children.

It is horrifying how few of these fourteen survived into old age. Three died in infancy and seven between the ages of 17 and 34. George Henry himself died in 1842 at the age of just 57, not long after he had inherited the estate of Clifton Hampden from relations of his mother; and Caroline eight years later at the age of 55. The history of the family is littered with references to typhoid fever or just “bad health”.

Several of the boys went into the family business, which had been set up by George Henry’s father Antony to trade with Spain and (from the time of the Napoleonic Wars) South America. The business had had a chequered history; Antony had gone bankrupt in 1789. The family voluntarily decided to honour the debts, which were finally repaid only in 1840.

But then their fortunes changed: they stumbled on the potential of guano as a fertilizer: “Mr Gibbs did make his dibs, selling turds of foreign birds” as the Victorian music hall ditty went. The eldest of George Henry’s sons, Henry Hucks, lived in style in what became the American ambassador’s residence in Regent’s Park. George Henry’s brother William built Tyntesfield, the great house near Bristol that is now owned by the National Trust; and he paid for the building of Keble College in Oxford.

The grave tells how there seems to have been an expectation that the sons should go into the family business. But there was also a keen interest in the Oxford Movement, as seen in the Keble connection; and several left the business to go into the church, being supported financially by their brothers in the business. Only Charles chose an independent career, as a soldier.

It is curious that, although not one of these nine people actually lived in Clifton Hampden, the place was obviously of such importance to the family that they wanted to be buried here. George Henry’s body was brought back from Venice where he had died when on holiday. Charles, the soldier, who had retired to live in London, chose Clifton Hampden as his burial place.

The Clifton Hampden connection had been a long one through George Henry’s mother’s family, the Huckses. In 1726, Robert Hucks, a brewer and MP for Abingdon, bought the Clifton Hampden estate from the Dunch family of Little Wittenham.

George Henry’s brother Joseph had come to live here in 1830 as a young priest, just 29 years old; he had clearly found that the family business was not for him. In 1846 he moved into the newly built Vicarage, which had been paid for by his sister-in-law Caroline, the house that is now the Manor; and he lived there until his death in 1864.

The one son of George Henry and Caroline who did live here was John Lomax, my great grandfather. He took over as the vicar here in 1865 on the death of his uncle Joseph. Just as his uncle had persuaded his brother George Henry to take an interest in Clifton Hampden by rebuilding the church, so too John Lomax persuaded his brother Henry Hucks to pay for the bridge across the river, the school (to which William also contributed) and the village hall.

There are many more Gibbs relations buried in the churchyard. Henry Hucks’s son Alban came to live here in 1905 when the Vicarage was expanded and turned into the Manor House and John Lomax’s son, my grandfather Reginald, the priest at that time, moved back into the Vicarage house from which Joseph had moved in 1846. Gibbses lived in the Manor until 2000. In the village lived a number of relations, notably the Pott family, and several are buried here. But I like to think that this huddle of Gibbses in the big grave, the first of the family to be buried here, would be happy to see the village they loved still thriving, albeit in new ways, three hundred years after the family involvement began.

Thank you to Christopher Purvis for this story. If you would like to make a contribution to the restorations at the Church of Saint Michael and All Angels, please contact Christopher for details.